Apple Award Winning Podcast

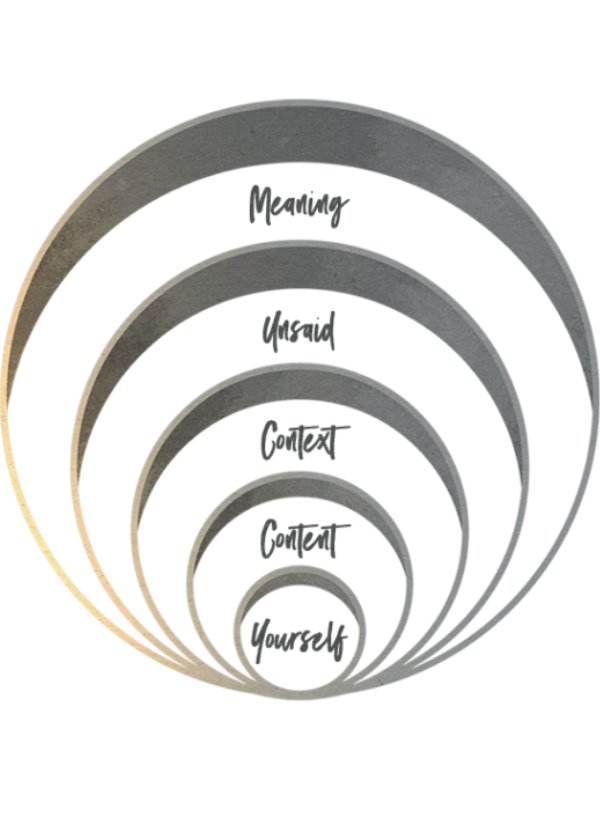

Listen: to yourself, for the content, for the context, to the unsaid, to meaning.

These are the Five Levels of Listening.

In this episode Oscar and Nell go through each of the five levels, explaining how they work individually, and as a whole, and how to move from one to the next.

Hear real stories about each level, how it fits together in the research, and flashbacks from previous podcast interviews.

Listen out for the practical tips for each level and discover where you are at on the journey to Deep Listening.

Transcript

Deep Listening Episode 52: The Five Levels of Listening – The big picture

Oscar Trimboli:

Deep listening – Impact Beyond Words. Hi, I’m Oscar Trimboli, and this is the Deep Listening Podcast series, designed to move you from an unconscious listener to a deep and productive listener. Did you know you spend 55% of your day listening, yet only 2% of us have had any listening training whatsoever? Frustration, misunderstanding, wasted time, and opportunity along with creating poor relationships, are just some of the costs of not listening. Each episode of the series is designed to provide you with practical, actionable and impactful tips to move you through the five levels of listening. So I invite you to visit OscarTrimboli.com/Facebook to learn about the five levels of listening and how others are making an impact beyond words.

Welcome to this episode of Deep Listening – Impact Beyond Words. Today we’re laying out the edges of the jigsaw puzzle for deep listening. Today’s an overview of the five levels of listening that makeup deep listening, and with me is my cohost Nell Norman-Nott and together we’re going to unpack what the five levels of listening actually are. Level one, listening to yourself. Level two, listening to the content. Level three, listening for the context. Level four, listening to what’s not said, listening for the unsaid, and level five, listening for meaning. And this is where you have an impact beyond words.

Today we’re going to provide an overview of each level of listening, and we’re going to start with level one, listening to yourself. Now, when I speak to people about what they struggle with the most, when they come and see me and after I present from a stage, or maybe it’s in a training course, in a board room with a leadership team, all of the people I’ve worked with say they struggle the most with what’s going on, churning up in their head and they’re struggling to stay focused in the conversation. All of them talk about their struggle with focus. Listen out for an interview with a Swedish sniper, Christina, in a future episode where she talks about the power of focus.

Christina:

In the fall of 2005, I find myself at The Military World Championship in shooting. I’m in the lead in the final, and I have one shot left to shoot. The target is 50 metres away and the 10 is 10.4 millimetres.

Nell Norman-Nott:

Wow. I can’t wait to hear that one, Oscar.

Oscar Trimboli:

She’s just amazing. Her ability to focus is extraordinary and a world champion and what she does as well. But back into everyday life for those of us who can’t be world champion snipers, we do struggle with focus. We do struggle with distraction. We do struggle with maintaining our attention. Thanks to the great research where we partnered with Heidi Martin, we discovered that it’s not only us, there’s 1,410 people out there who had participated in the research, and Heidi summarised so beautifully 86% of people struggle with staying present in the conversation. This is all about level one and level two. So now when you think about listening to yourself, what does that mean to you? Where do you have struggles?

Nell Norman-Nott:

To me, listening to yourself shows up in meetings. It’s about being aware of your emotions and the state that you actually enter a meeting room. It can be particularly tough to manage this when you rush from meeting to meeting, and I felt it when I was managing a team at LinkedIn and I had one on ones with my direct reports. And this was a company where we had a lot of meetings back to back. But there was also a big emphasis on managers to invest a lot in their direct ports, which is fantastic to nudge them, to develop them. But to be able to do that, you do really need to be present.

Oscar Trimboli:

Now, one on ones. Great example of jargon. For those people listening and don’t know what that means?

Nell Norman-Nott:

A meeting where you would talk just with the direct reports one on one, so hence the terminology. But thanks for pulling me up on my jargon. They were regular catch up meetings that I’d do with my team to discuss projects that were running and their work that was going on at that time. So particularly I wanted to talk about one occasion when one of my direct reports, Sophie, was really unhappy not to be approved for a promotion, and she was pretty upfront about it. It made it actually quite a difficult meeting.

After some time talking it through and the rationale, she did accept it. But I’m someone that’s empathetic, and I’ve learned over the years that after a situation like that, I need to really listen to myself to understand my own emotions and to reset before I can go into another meeting, because I can take all of that emotional baggage really, almost with me. When I was listening to podcast 32 with Jen Brown, she talks about listening starting with understanding one’s own emotions.

Jen Brown:

Listening for four major points that need to be present for anything to move forward, whether it be improv or a regular conversation. It’s who you are, what your relationship is, where you are, where you’re actually located, how you feel, what your emotions are around the situation, your location, their relationship, and what you want. What’s that thing that’s driving you? Whether that be a sandwich or a cookie or something bigger than that, like love or affirmation or attention.

Nell Norman-Nott:

It was this experience that made me reduce all of my meetings with my direct reports down to 45 minutes, and that gave me time … not only did it give me practically the time that I needed to cover the content because 60 minutes had probably been too long anyway, but it gave me 15 minutes to take time out between meetings to really dissolve any acts that I might’ve taken on in difficult conversations. I think it’s not uncommon for women in senior leadership roles who are managers to be empathetic. It’s something that I think is a real attribute. Oscar, I suppose, am I alone in struggling with this, and how does it fit with the five levels of listening?

Oscar Trimboli:

No. Great news, you’re not alone. I’m here-

Nell Norman-Nott:

Yay!

Oscar Trimboli:

… with you.

Nell Norman-Nott:

Thank you Oscar.

Oscar Trimboli:

That is really common. It’s common in the people I work with on consulting assignments, it’s common in facilitations that I’m part of with leadership teams. It’s common when you’re in those situations where you’re meeting with somebody else, as you said, one on one. But I would say 86% of people that we interviewed in the research struggled exactly the same thing, so where does it fit? It fits into level one, listening to yourself. And I think that little adaption you made by reducing your meeting time to 45 minutes is really skillful. It’s really clever. It’s a really thoughtful way to help prepare you not only to decompress from the last meeting that you’ve had, but also to prepare you, to set you up to be completely present for the next meeting that you’re going to come into.

Big shout out to Donna McGeorge and The 25 minute Meeting Book. She’s got a great book to talk about how to build a process to make meetings even more efficient, to move them to 25 minute meetings, rather than an hour or even 45 minutes. So Donna has got some great tips, and you’ll be hearing from Donna in some future episodes as well, which she talks about, how do you listen in meetings to make them really effective?

Nell Norman-Nott:

Well, I’m going to go and get that book, Oscar. I think a 25 minute meeting sounds fantastic.

Oscar Trimboli:

So coming back to this issue around level one on listening to yourself, it’s one of the things we have to think about when we come to the five levels of listening, and it’s something I’d say to everybody … in a perfect world, I would say, everybody needs to master each level before they proceed to the next level of listening. But we don’t live in a perfect world now.

Nell Norman-Nott:

Unfortunately no.

Oscar Trimboli:

We’re all juggling. It’s not perfect. It is messy. What we want to understand is the deep listening model with the five levels of listening, it is foundational, it is sequential and it is progressive. The more you can master level one, the bigger the platform you set up for success. In very high level sporting organisations, they talk about this concept that is the broader the base, the higher the apex, which means the more participants you can bring in at junior level sports, the likelihood is the more chance you’re going to have peak performance at Olympic level. And it’s the same with deep listening. The deeper the base at level one, the faster you can get to the other five levels of listening. So, level one is and something we should skip over or assume is easy. In fact, it is the hardest level to listen at, listening to yourself.

To get the biggest bang for buck when it comes to listening, let’s start with level one. That’s where we build this really strong foundation. So no matter how you’re listening, no matter where you’re listening, no matter what relationship you’re in with the person you’re listening to, you want to be on a really sure footing to become a deep listener. Your single listening at level one, listening to yourself, it starts with you, not the speaker.

No, you’ve probably attended more music concerts and performances than I have. You probably turn up early, you probably get ready to listen. Rarely would you think about turning up to the concert at exactly the time it started, unless it’s maybe a Wiggles concert.

Nell Norman-Nott:

Those are the kind I go to mostly.

Oscar Trimboli:

You wouldn’t want to turn up light. And if you turn up light to The Wiggles, I’m sure Finn would have something to say about that. So you turn up early, and it’s the same with listening to yourself. You wouldn’t turn up with a set of headphones when you go to a concert. You’d make sure you’re prepared to listen, and you don’t have a bunch of noise in your head before you’re ready to listen to somebody else. But the reality is most people treat conversations in a way that they turn up late. There’s a completely different song playing in their head or a story that’s completely different.

And that means you can never listen to the other person fully because you’re listening to the story that you’re telling yourself in your own head. You’re telling yourself a story about the past, the present, the future. You might be telling yourself a story about, I don’t get on with this person. So you’re already disconnected from your ability to listen. So now, I reckon getting ready to listen to yourself is the most important thing any of us can do. So here’s three tips, really practical, really simple, something you can all do the minute you finish listening to these podcast. Number one, the deeper you breathe, the deeper you listen. Just become a little bit comfortable with taking in that breath for five seconds longer, holding it for five seconds longer.

Nell, I’m not asking you to become a yoga instructor. I’m not asking you to sit cross legged before you go into listening to anybody, but just take a little bit longer. Five seconds. Five seconds longer. Slow down, breathe deeply for five seconds down into your diaphragm and hold it there for a little bit longer than it’s comfortable. And then imagine it moving from the right hand side of your diaphragm to the left hand side, and then release. It’s a technique called box breathing. Box breathing is done by elite athletes, it’s done by navy seals, it’s done by opera singers. So anybody who wants to have great control of what they’re thinking about will do that.

So high performance breathing is really simple, but it’s something we have to practice. The deeper you breathe, the deeper you listen. And when I’m training, people ask me, so why? Why would I bother? It’s really simple. Listening taxes to the brain. Because we haven’t been taught how, it’s really difficult for the brain to listen, so the more oxygen we can get to the brain, the more capable the brain is to listen. So the deeper you breathe, the more oxygen you get to the brain, the more oxygen you get to the brain, the easier it is to listen. Thanks to that commercial break from The Neuroscience.

Tip number two, get hydrated. A hydrated brain is a listening brain. Drink water. Always have a glass of water with you. As you can see in the work that Nell and I are doing right now, both of us have a glass of water next to each other, and we’ve been very deliberate about hydrating. Again, the commercial break from Neuroscience makes it really simple. The brain consumes 25% of the blood sugars of the body, yet it’s only about 5% of the body mass. So it’s a really hungry organ, and make sure it gets blood sugars in there.

When you’re doing something as difficult as listening, the brain is consuming more blood sugars faster, so get water into your system. A hydrated brain is a listening brain. And hydration is not defined by coffee, people. I know some of you love Starbucks. If you are going to drink coffee, then you’re going to have to drink a glass of water extra for every cup of coffee you have because coffee is actually something that’s going to dehydrate your body.

Nell Norman-Nott:

When I very first met you, you talked to me about deep listening and I said, “Look I’ve been doing all this, Oscar, and I’m really tired,” and you said, “Yeah, it’s hard work.” Today’s techniques must help, just by breathing and by drinking water, it must help with that as you get better at it.

Oscar Trimboli:

Yeah. I remember I was doing a presentation down in Melbourne. There was about 400 people in the room, and it was just before lunch and a lady came up to me. She said, “Well, you started talking about the deeper of breathe, the deeper you listen, and I thought that was the biggest load of rubbish,” she said, “but I was stuck in the room. I was a hostage for the next 45 minutes listening to you drone on. And I thought, ‘Well, what have I got to lose? I’ll just practice what this joker’s said from stage.'”

And she made a reflection that you made. She said, “Oscar, I started noticing the sound of the air conditioning in the theatre. Oscar, I started noticing the vibration of the mobile phone from somebody three seats down from me. Oscar, I started to hear things myself in my own head that I’d never heard before. But the thing I noticed most was it was actually easy to listen.” So a hydrated brain and a brain one full oxygen, listening becomes much, much simpler. But we don’t realise that.

So getting oxygen to the brain is going to make it less tiring for you. A lot of people struggle with listening because it is. It’s tiring, it’s distracting because we’ve never been taught how. In math, we know plus and minus and divide and subtract, but nobody knows what that is for listening. So that’s what the five levels of listening are all about. So we’ve talked about number one, the deeper you breathe, the deeper you listen. Number two, we’ve talked about a hydrated brain is a listening brain. And number three, this is the thing all of us can control. Switch off the mobile phone.

I’ve been working with some of the most senior executives in the world. Reminds me of a story where Peter, who was a visiting Microsoft exec who ran an organisation of 55,000 people came to Australia. I was hosting a meeting with 10 executives. He sat down at the room I was hosting and was just about to start talking and apologised to the room, stood up, took his mobile phone, or his cell phone as Americans would call it, out of his top pocket and switched it off and then put it in his bag. And he said, “The most important thing I can give you all is my complete attention right now.” What do you think happened for other 10 people in the room?

Nell Norman-Nott:

They’d mirror that behaviour.

Oscar Trimboli:

Yeah. So seven out of 10 people switched off their phones. Three out of 10 didn’t, but you could hear a pin drop in the conversation. There wasn’t people talking over each other, there was listening taking place. And if somebody who runs an organisation of 55,000 people can switch off their mobile phone, so can you. So, whether that’s an iPad, whether it’s a laptop, just keep it completely out of reach. That would be the thing. If you can get it out of eyesight, even better.

Now it also reminds me of another story, when I interviewed Christina in episode eight, a foreign language interpreter from Sao Paulo in Brazil. And she does lots of interpretations across many nationalities. Her range of languages is amazing. Portuguese, Spanish, English, Italian, French, Polish. She’s just got this amazing brain when it comes to languages. And as you can imagine, she does these translations, interpretations in real time, typically in the finance sector, but not limited to that. Typically in mergers and acquisition situation, and so there’s lots of money at stake, millions and billions of dollars. Let’s all have a listen to how Christina prepares to listen when she’s doing something really complex.

Christina:

Breathing is absolutely essential. Part of my meditation routine when I’m in the room, actually, when I’m about to start my interpreting, is to take at least three or four very deep, deep breaths. I do the classic meditation routine, where you inhale for about eight seconds, you hold your breath for another eight, exhale for another eight, and then wait another eight seconds to breathe again. And I do that at least three or four times because it’s just super quick, and it also helps relax my muscles, relax my body. Especially because if your shoulders are tense, or if your neck is tense, that also prevents you from allowing your voice to come out and to channel out more properly too. So definitely breathing is key for me.

Oscar Trimboli:

So level one listening is about listening to yourself and those three tips. I’ll say again, the deeper you breathe, the deeper you listen, a hydrated brain is a listening brain, and switch off the electronic devices. Be completely present for those in front of you.

Nell Norman-Nott:

Oscar, the thing that really stood out for me that you were just talking about was the mobile phone and just putting that down. I see that with my kids, and I feel that in myself. There’s that pull to go back to my phone and to check it, whether I’m waiting for an email from my lecturer because they’re responding to me about an assignment, or whether I’m waiting for some feedback from you, Oscar, about something I want to post to the Facebook group. There is a constant pull there to check your phone so when you need to be present, what great advice to just switch it off. And I think that’s really important when we’re at home with our children because we all feel that as parents, to keep checking and keep looking.

Oscar Trimboli:

Yeah, that’s a great point. And we’ve interviewed an expert in working with kids. Listen out for an episode with Doctor Justin Coulson. He gave some great practical tips on the episode, so make sure you listen out for that one. But here’s a tip that I talk to the executives I work with. When you get home, the first thing you do is you put your keys in the same place. It’s usually a bowl or somewhere near the front of the house. Do exactly the same with your mobile phone.

Nell Norman-Nott:

That’s great advice, Oscar. Thank you.

Oscar Trimboli:

Level two, listen for the content. Most of us can see in colour, but equally most of us just listen in black and white. Black is what we hear and white is what we see. We want to make listening much more than a two dimensional. We want to make listening completely technicolour. All the spectrums of colour in what we see, we want to be able to get to that when we listen to the content. Listening to content is much more than just listening to words, sentences and stories. Listening to the content is making sure you can notice the alignment and the congruency between what somebody is actually saying and how they’re saying it. It’s the connection that you notice between their head, their heart, and their gut.

What energy are they speaking to you with? And for people who listening colour, they’re sensing, they’re feeling. They’re doing so much more than just listening to the words. It reminds me of the fantastic mandarin character called Ting. Not to be confused with Nell’s friend Ying from the previous episode, but Ting is a mandarin character, which means to listen. Ting from the ancient Chinese going way back to the third century BC, is a six dimensional character, and only two dimensions are about physically seeing and physically hearing. The other full senses that Ting talks to are about presence, feeling focus, and respect.

Being able to listen to all the elements of Ting in the dialogue means that you not only notice how you’re feeling, but you can notice how they’re feeling as well. So if you’re struggling listening in black and wine and full spectrum technicolour is something that you’re going to struggle with, six dimensions or six colours of listening through Ting is a great way to do that. And with all my respect to people from China, nobody in China would ever deconstruct Ting into its six characteristics. Only Westerners would do it because Chinese are all about the integration, but when we’re starting to learn in the West, the first thing we do is we deconstruct things into their smaller component parts. A bit like the Lego blocks of listening.

Most of the listening literature now, whether it’s books or tips and tricks, all talk about listening for the content and listening to the speaker and they jumped level one listening all together. This is where most literature on listening starts and unfortunately, this is where most of that literature also finishes. A lot of the active listening movement of the ’80s and early ’90s comes from this orientation, and we want to show a wholeness beyond those levels of listening. So if you’re only listening to the words in this discussion, you’re listening is really one dimensional. It’s like a table tennis game or a ping pong game, depending on where you’re from. It’s really energy sapping.

It is a back and forth, and back and forth, and a continual back and forth until some point at which somebody wins the conversation, and then you start all over again and everybody’s totally exhausted. Holly Ransom summarised this beautifully in episode 42 when she talked about listening to the energy of the global leaders that she interviews. You see, Holly’s from a generation still in their 20s, and she’s had the opportunity to interview some of the most amazing leaders in the world. Let’s listen to how she interviewed President Barack Obama.

Holly Ransom:

One of the things that strikes me about leaders, and it’s probably something I listen for a lot as much as people might go, “Oh, that’s a strange thing to listen for,” I listened for energy and I listen for a sense of how convicted, I believe, someone is in what they’re talking about and from there, I think as well a sense of how well they know themselves and the things that they stand for.

Oscar Trimboli:

So here’s the question for you. How much time are you spending listening for the energy in the dialogue? Now, one of the things we don’t spend nearly enough time listening to when we’re listening to content is actually listening to silence. Great music has lots of silence in it. Great conversation has silence in it as well. We need to treat silence just like another word. I give it full respect. I listen to it completely. I give it care. I give it reverence. Silence is there because it helps the speaker collect their thoughts.

Remember, a speaker can speak at between 125 to 150 words a minute, and if you auction cattle, you’re probably speaking at about 200 words a minute.

Oscar Trimboli:

You can listen at 400 words a minute, and here’s the really critical point. The speaker can think at 900 words a minute. So the likelihood that the very first thing they’re saying is brilliant articulation of what’s actually in their mind without any preparation or rehearsal, there’s about an 11% chance that they’re saying what they’re actually thinking. I don’t about Nell, but if a doctor gave me an 11% chance of surviving a surgery, I’d be asking for another opinion.

Nell Norman-Nott:

Yeah, absolutely.

Oscar Trimboli:

You mentioned earlier that listening to silence is something you developed from a young age. What I’m really curious about though, is how did you become comfortable with the silence, and have you got any tips around using silence?

Nell Norman-Nott:

Silence can be intimidating because it feels quite unnatural being comfortable with it. It just comes with practice. Like everything that we talked about today, there isn’t a magic thing that you can do, but there are some really useful tactics. So the most useful one, I think, is just counting. Wait after the person’s finished speaking and in your head, count to three. Sometimes you might find that the other person says something else and as you get more used to this method, you won’t need to count and that time can be used for reflection as you were saying before, Oscar, so that you can think about what’s being said, and it will help you listen more deeply and collect your own thoughts.

I think it can work in a lot of different scenarios. It’s particularly useful in business and reminds me of when I worked in England in 2006. I worked for a franchisor, and the biggest challenge in running a franchise is maintaining a relationship with your franchisees. They’re the sales funnel and without them the business doesn’t exist. But the franchisees have invested huge amounts of money to buy the business from the franchisor and all of the licensing and all of the marketing. They’ve maybe spent $100,000-

Oscar Trimboli:

Wow.

Nell Norman-Nott:

… on buying that. I know. And it’s great because they get this fully fledged business model. There’s a sense of ownership on behalf of the franchisees, who’ve obviously spent a substantial amount of money, and that can cause friction with the franchisor because the franchisees have their own opinions about what they want. So my boss at the time was Greg, and he’d been running the franchisor business and had grown it to 150 white collar franchises. A franchise that’s all across the UK and in Ireland.

In listening to the franchisees and their pursuit of having their own prosperous businesses, Greg realised that mindset of the franchisees might be a problem. Many franchisees felt there wasn’t enough business, but really, Greg knew that only 2% of the market potential had been tapped, and there were 98% of businesses that the franchisees could still tap into. So, Greg embarked on offering all franchisees and every new franchisee that bought a franchise a mindset training course. And as someone who worked in the head office with Greg, I got to go on the first training course that ran. And it was here that I met Liam.

Liam had been a senior executive, and he could tap into his network for leads to build his franchise business. But his demeanour was dour. However, at the end of the mindset training, we revealed something that we’d taken away from the training, and it really stuck with me because Liam said, “I was told as a child I wasn’t a natural smiler, but I feel different now after the mindset training, and I feel like I can change that.” And as he said that, Liam gave this massive smile. And it was interesting because that moment marked a real change in Liam and a change for his business.

I just looked at Liam’s LinkedIn profile the other day, but you know what? He’s retired now, and it says that he’s happily so. I just think that this is a real credit to Greg for listening to what the franchisees actually needed and identifying that … he could’ve got cross with them for being difficult and wanting to do something different to what he believed, but instead he turned that around and said, “Hang on a minute, let’s shift your mindset. There’s 98% of business out there.”

Oscar Trimboli:

It seems so basic now, doesn’t it? Listen to your customer, listen to your staff, listen to your franchisees, listen to Liam, listen to your resellers. I see this as one of the biggest challenges that leaders face when it comes to listening. They spend a lot of time hearing what people say, but it’s all for nothing if listening isn’t actually actioned. Employees, customers, franchisees, resellers, even voters get frustrated when they say something and it’s not acted upon. I think the big distinction here is that Greg took action on what he actually heard, and the difference between hearing and listening is action.

Nell Norman-Nott:

That is so true Oscar because I … coming from working in corporates, I experienced a lot of research being done, but how many companies actually act on that?

Oscar Trimboli:

You make a great point, Nell. Episode six, Michael Henderson, corporate anthropologist talks about this exact point, employees being surveyed to death and nothing being done with it.

Michael Henderson:

I’ve got a real concern about how organisations are using engagement surveys. I think you need to be very, very aware of the context in which the questions are being asked. If you sit around a fire in a traditional culture, the questions that are used around that fire to entertain or to inform or to educate or simply just to connect and share are always contextual. So the people who are asking the questions are in the culture, and so they are often able to select even the right phrasing of the question to elicit the response that they’re looking for. Whereas you find it with the organisational surveys and engagement surveys, the questions I usually generic, not customised. They’re used to design to measure in comparison to other cultures, which anthropologically speaking is bordering on insane. You can’t compare one culture with another in terms of metrics, so it seems really bizarre.

Oscar Trimboli:

Nell, you’ve just prompted me because a lot of my work inside organisations, particularly with senior executives, they often plan running what they call a listening tour, and for those of you can’t see me, listening tour is in air quotes. It’s one of those bits of corporate jargon that you hear a lot of and you also hear it from politicians. And the thing that makes the difference between a great listening tour and a good listening tour, you need to dedicate as much time to hearing from staff, from customers, from voters, from suppliers, from resellers as you do to an action plan.

So if you’re spending four hours listening to people, you need to set aside four hours for the action plan and part of that is communicating the action you’re going to do. And if you’re spending a week doing a listening tour, then you need to dedicate a week to the action plan because then people know that you’re being serious about listening and that will create energy around the change you’re trying to bring. A really good example of this comes from Hugh Forrest in episode 45, who works for the global vent organisation South by Southwest.

Hugh Forrest:

The PanelPicker is an interface, again, that we developed about 10 years ago. Anyone who could get online can enter a speaking proposal, and there was about a month long period where these speaking proposals can be answered and we have about two weeks where we polish up everything that’s been entered, and then we have an interface where all those ideas are displayed. And again, it’s in the neighbourhood of 5,000 total ideas.

Oscar Trimboli:

He spends six weeks analysing thousands and thousands of attendee feedback. They start to distil down over 5,000 ideas for speaking ideas for the next year because they have to take the 5,000 and make them into just over 100. What a commitment to listening he’s making, six weeks a year to listen to feedback. This little wonder has catapulted Austin, Texas from being a relatively small city in Texas, in the United States, to now being the 11th largest economy. Not completely based on South by Southwest, but definitely a big contribution and a great legacy from Hugh. Listening matters.

So here’s my three tips for listening to the content. Number one, face the person you’re speaking to. We’re doing that right now, Nell. Make sure your eyes are facing each other. We’re doing that right now, Nell. And this means your ears are actually at the same level, so you’ll have unobstructed hearing too. Tip number two, listen to the words, the body language and the energy from the speaker. He said aligned is a congruent with what you’re feeling. A bit of that gestalt that you were talking about earlier on. Tip number three, listen to the pause, listen to the silence. Do it completely, do it fully and do it respectfully here as well.

Level three. Listening for the context is about the backstory. It’s about what comes immediately before and after what’s being said. The context is the situation in which something exists, something happens, and it’s something that helps to explain it. Context is the influence around the events, as well as what’s happening at that point in time. If you understand the Latin origin of the word context, it means to weave together. And when you weave together the backstory and what you’re listening to in the moment, the context of mergers as a really powerful impact in the dialogue.

Context, it’s about patterns in language. It’s about patents that spans culture, teams, organisations, languages, how you think about time. Whether you think about the past more than you think about the future, whether you speak about people as individuals or as collectives. It’s about unlocking this context, and if you can unlock the context, that’s the difference between a conversation that feels frustrating, almost circular … it feels like you’re in an aeroplane, in a holding pattern, just waiting to land, wasting fuel and going around and around and around. No matter what you do, you’re losing energy and the conversation feels like it’s going nowhere. We’re always looking for the missing piece in the Jigsaw puzzle when we’re listening for context. Context has a dark side too.

The context of not listening can cost a quarter of a million lives. In July 1945, the allied commanders had submitted the surrender proposal to the Japanese prime minister and the terms under which they expected the Japanese armed forces to surrender. The Japanese prime minister held a press conference and use the word-

Oscar Trimboli:

… during a press conference. These words can have multiple interpretations and context depending on how they’re being used. One way this word could be interpreted is you want to ignore people. You want to show contempt, you want to take no notice of them. Unfortunately, that word can also mean no comment and it’s something you’d expect a prime minister to say at a press conference full of journalists, yet the allied interpreter misinterpreted the context and interpreted the context of the word to mean ignore.

The allied commanders were told by the translator that the Japanese were planning to ignore the terms of the surrender. The allied commanders as a result, made a fateful decision. They made a decision to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki. You see, the cost of not listening for a simple word-

Oscar Trimboli:

… cost 250,000 lives that were lost one month later in August 1945 in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It’s a painful story to tell when I think about the carnage and the wasted lives and the cities and families that were destroyed all because the context was missing. And the consequences for not listening to the context where huge. It’s important to listen for the context. Do you understand the context? Are you listening for their context? Are you listening for your context? And are you listening for the context of the conversation?

So much of it is about the substance, what people say, but equally there’s a nuance. The essence of context is three dimensional. Your context, what are you bringing to the conversation? Their context, what’s their backstory, what are their assumptions? And then finally, what’s the context of the conversation? Or as I like to call it, the DNA of the dialogue. The most important thing to understand that … look, a conversation’s organic. It’s a three dimensional dance, and there are many opportunities for understanding and there are just as many opportunities for misunderstanding, for lost opportunities if you’re not aware of what’s happening, where somebody is coming from, because dialogue is simultaneous.

Every conversation your speaking and listening to happens simultaneously. It’s all happening at exactly the same time, and if you’re not conscious of level three and the context and listening for it, the conversation will break down. Your context is bound by your assumptions. Some of these assumptions you’re conscious of, some of these assumptions are explicit. Some of these assumptions are declared, but usually most of them aren’t. We’re not even aware of our own assumptions that we bring to the conversation, let alone the speakers assumptions.

In our modern world, we’re more connected than ever over the internet and as a result, assumptions exist not only in a local context but also in the global workplace connected by the internet. As a result of operating in a global environment with global workforces, there’s more opportunity for confusion than ever as we work across cultures. Nell, I know we can’t have favourite children, but I know that this is one of your favourite podcast, episode 27 where Doctor Tom Varghese talks about the impact of culture.

Nell Norman-Nott:

Episode 27 where Tom Verghese talks about high context and low context cultures. He explains how in a high context culture, yes, doesn’t always mean yes. It can be maybe, and it can actually be no.

Doctor Tom Verghese:

Low context cultures are where yes means yes, no means no and no, and I say what I mean and I mean what I say. I get to the point, I’m direct. That’s if you think about the extreme symptoms of low context. High context is where yes means yes, yes, may mean yes, yes may also mean no, and yes may mean maybe, depending on how it’s said. So it’s contextual. So it’s not just what’s said, but it’s the tonality of the voice, the pitch, facial expressions, body language.

Nell Norman-Nott:

When I was travelling in India with my husband Jerry back in 2008, we were travelling from Delhi to Agra to see the Taj Mahal, a bit you will be in a few weeks, Oscar, when you go to India. We were on a budget, so we decided to take public transport, and we asked at our hostel, if we turned right out of the building for the train station, will we get there? And the very helpful person on reception and nodded his head and said, “Yes, yes, yes.” But what I noticed after about an hour of us walking with our backpacks on in 30 degree heat was that we hadn’t found the train station.

What I realized … and this came from a perception that I generated just being an Indian talking to a lot of people there was that maybe the person that we’d asked on the reception desk hadn’t felt comfortable saying he didn’t actually know how to get to the train station. And this had happened previously. Been a scenario that had played out before and continued to play out through our trips, was that people who didn’t know just nodded and said, “Yes,” because they didn’t really feel comfortable saying no.

Oscar Trimboli:

Yeah, Nell, that’s great. And I’ll definitely keep that in mind when I go and visit Sean, Jennifer and their grandson Sebastian in India in a couple of weeks. And I experienced that first hand myself in Indonesia in about 1995 in similar scenario, where yes, just meant yes. They acknowledged that you’re speaking to them rather than yes, they understand what you’re talking about. And again, that’s a really great highlight as Tom talked about, that when you come from a low context culture like Western cultures like Australia, like the United States or Canada or even the United Kingdom, when you operate in high context cultures such as a lot of Asia, the Maori cultures, the Aboriginal cultures, languages, much more nuance.

But more importantly, the relationships matter more, so if you would have invested a bit of time to get to know them, you might have got a more specific answer, which was what I was taught by an old boss, Steve in Indonesia at the time when I was asking for directions as well. He says, “Oscar, you don’t ask for directions. You build a relationship, and then they’ll offer that to you.” So, it’s a good insight.

Nell Norman-Nott:

It’s a fascinating insight. I think, never underestimate the value of really understanding that cultural context and … yeah. I think we had three months in India, and I don’t think we’d even cracked the surface of understanding the culture there. Another place this got brought home to me was when you and I were talking, Oscar, and we were talking about plans for this year … gosh, that feels like ages ago now. And you said, you wanted to do something. Can’t remember what it was now, but it was vitally important to you. And I said-

Oscar Trimboli:

Probably 100 million listeners.

Nell Norman-Nott:

Probably…Okay. And you said to me, “The way that you’ve just said, ‘Okay’ is very revealing. Do you really mean, okay?” I’m really interested in, Oscar, what were you thinking during that moment?

Oscar Trimboli:

When you said, okay, I noticed in your voice there wasn’t that surety, that confidence. There was a bit of a quiver in your tone. But what I noticed is in your voice was also concern, confusion and probably no clarity because I hadn’t provided it to you. So I thought when I heard this, there was a disconnect between what you were saying and how I felt it in the moment. So for me, I chose to pause and in my head I was thinking, “I wonder what’s going on for you right now.” It made me curious, and that’s when I said, “Do you mean okay?” And I was curious what was going on for you in that moment.

Nell Norman-Nott:

For me, I felt heard. And that’s really important in that kind of situation, I think. I felt it was an opportunity for me to ask more questions, which is really important and to delve in more because I did have questions in my mind and the ‘okay’ was more replacing those because I didn’t know how to articulate them at that moment and didn’t necessarily feel comfortable. But just by you asking that question, I could.

Oscar Trimboli:

Three tips. Ask for the backstory, rather than being confident and going ahead and making sure the conversation’s going through quickly. Joining a conversation halfway through is like trying to retrofit the characters and the plot from a TV show or a movie that happens to be playing and you jumped in half way. Just be honest, be humble. Just ask for the backstory. It’s as simple as saying, “Could we start at the beginning?” Takes a lot of courage to do that. You need to put your ego in your pocket, but asking that simple question, “Is this where the story starts?”, or “Should we start at the beginning?” helps them to think a little bit more.

Number two, listen for patterns. Listen for patterns in their language. It will help you understand how to make sense of their story, but more importantly, how you can make sense of the story for them as well. For a lot of us, we tell stories, but we don’t know what that means for us. So taking the time to notice patterns about past, present, and future will help you understand the context better for you and for them. Tip number three, explore the power of questions. Ask more how questions, ask more what questions. Nell, I see way too much of this in the workplaces, too many why questions? Lots of why questions, why this, why that? There’s even a methodology called the 5 Whys. There’s a methodology called six sigma. They are all about asking why based questions. I learnt from Alan Stokes in episode two, that why questions are laden with judgement.

Alan Stokes:

Why questions are loaded with judgement quite often. Not always, but 90% of the time. Why do you do that? Why are you asking me in that tone of voice? Why did you decide to stay with your abusive wife or husband? Why didn’t you do this? As you can see in all of those questions, there’s an implied judgement , an implied negativity. It’s not a positive nonjudgmental approach. It’s an approach that somehow comes with baggage.

Oscar Trimboli:

Why questions have their place, don’t get me wrong, but you need to be in a great relationship with someone to ask those questions. If you’re new to the relationship or it’s a commercial relationship, explore the how and the what questions in much more detail than you explore the why questions. There will be a time for why questions, but it’s using not right at the beginning.

Level four listening, listening for what’s unsaid. And level five listening to meaning. Nell, you and I are aware that from the research we did with about 1,410 people, 86% of people are struggling at level one and level two. So what I learned in this research is level four and level five, it’s ambitious, it’s aspirational, it’s inspirational for most of us. Listening to the unsaid and listening for meaning takes the patience of a monk and the tenacity of a marathoner.

It’s interesting having run a few marathons myself, and I know that only half a percent of people who try marathon has ever completed a full marathon. And I think this plays out in our research as well because I saw that only half of 1% of people are even aware, or have a language that is capable of talking to level four and to level five listening. So for some people, they know it’s possible, but that’s only half of 1% of people are even aware that level four and level five listening are possible. I guess it’s the same percentage of people who’ve completed marathons, but it doesn’t stop hundreds of millions of people every year enjoying running.

It doesn’t stop them to try to get better every day to be their best every time they lace up the shoes. And the same is true when it comes to listening. For me, I don’t believe I’ll ever become a deep listener. I’m always trying to be better, don’t get me wrong. I’m trying to be better in the next conversation and the next day and the next week, the next month, but I get distracted. I get triggered sometimes when somebody says something that I fiercely disagree with in the middle of the conversation. And I guess Nell, the difference between a deep listener and a recreational listener is deep listeners notice faster when they’re distracted, and they have a bag of tricks like breathing deeply, like drinking water, and not having distractions to help them get back into the conversation.

Now, one of the stories that brings level four and level five together for me was in March 2014. I was in a really narrow cramped boardroom in Melbourne. In the CBD, there wasn’t any natural sunlight, there weren’t any windows in the room and it was one of those that you always had to figure out, going to get this air condition to work.

Nell Norman-Nott:

I know those kind of rooms.

Oscar Trimboli:

We were just before the lunch break, and I could feel the oxygen had been sucked out of the room rapidly. People were struggling to focus, people were struggling to stay in the conversation. There were 11 people in the room and myself working together. We’d been going since 8:00 in this meeting, and the meeting was a workshop to figure out the future of this technology organisation with 300 people. Look, for the past decade, they’ve been doing really well. They’ve been growing, but more recently, their growth had flattened out. So one of the exercises I do to explore what’s meant in the future, I ask them to describe this future organisation that they’re part of as an animal.

Now, everybody picked a bird, a bird of prey. A fast bird, a sweeping bird, an elegant bird, an eagle, an osprey, a seagull. They picked the fastest moving birds possible. So what we did, we asked everybody in the room what animal they were thinking of. I noticed though, there was one person in the room who hadn’t spoken. This was Eileen. Eileen was thoughtful. She was deliberate. She was the kind of person in a meeting, when she speaks, you want to hear what she says. When she speaks, you want to hear what she says because she listens so deeply. She’s really considered, she’s really well thought through. Equally, she’s quiet and reserved.

And in that moment, I had a choice. We were close to lunch, the room was frustrated, the oxygen was out of the room, and I could sense the CEO wanted to move on. And his body language was giving me those signals, “Can we move on?” But in that moment, I chose to explore what was unsaid. And in that moment, I chose who wasn’t saying something. So I turned to her, I paused, I glanced at everybody in the room except for her and I waited. I deliberately held the pause, and it probably felt really uncomfortable for everybody in the room. It probably felt like an eternity. In reality, it was maybe 10, 15 seconds of silence. And I made an offer.

I made an invitation to Eileen and I said, “I’m curious, would you like to offer an animal to the group?” Look, Eileen had thought about it deeply. She took in this huge, deep breath and then she exhaled. And she said, “Well, I thought it was obvious that everybody is different to me. I thought we’re a snake.” So now what’s going through your head when you hear a snake?

Nell Norman-Nott:

Well, snakes are slimy, they’re deceptive, they’re creeping around trees. I think that they’re not very trustworthy.

Oscar Trimboli:

And I think for you listening, you’ve probably got exactly the same perception. And for the 10 people in the room, I can guarantee you they were thinking about the same thing. And again, deliberately holding the silence in the room long enough that it was deafening. The tension in the room was increasing. I remember looking at the CEO and he was holding his breath, and although I’m comfortable with silence, it was really obvious the rest of the room wasn’t. But I held it a little bit longer and then a little bit longer again. And then I said to Eileen, “Tell us some more.”

So she continued. She said, “Look, it’s obvious to me that we’re a snake. We adapt, we evolve, we change, and just like a snake, we shed our skins every season. We shed our skins to adapt for what our customers need from us. And it’s in this adaption that we’ve been successful. The whole room breathed out, Nell, the tension completely left the room, and the energy dramatically changed. The dialogue changed in the room, and people started to have a conversation about what’s good about a snake. So now, what’s going through your head when you hear this story?

Nell Norman-Nott:

I love that story, Oscar. And you’ve said it to me before, that the person that’s the quietest in the room often has the most value to add to the conversation, and the advice that you’ve given to me is to ask that person to speak up and to invite them to be part of it. Having worked in lots of corporates and organisations, we do make a lot of change and it’s not uncommon like Eileen explained. We’re shifting and we are changing shape, but as a marketer and having worked in marketing for 15 odd years, you do need to be mindful about listening to your customers before going and making those changes because changing something just because you think it’s not working or you’re bored of it is not necessarily the right basis to shift an organisation.

But I’m really intrigued, Oscar, how did this finish up with Eileen and with the company?

Oscar Trimboli:

Well, the company adopted the snake shedding its skin as a theme and as a result, they credit a lot of their growth, double digit growth over the subsequent years since then. They adopted snake names as code words for product releases and release schedules. Snake became a beanie toy and a mascot for the staff. They even incorporated snakes into the logos that they use for customers presentations. So a couple of tips, I would say, that it’s come out of this, make sure you listen to all the opinions in the room, Nell. Make sure you’re listening not only to what’s said, but what’s unsaid and who’s not saying it.

And although people are quiet, silence doesn’t mean they don’t have anything to say. Equally, silence can be a potent way of drawing the group into thinking deeply about the challenges that come next. Ultimately, the theme about the snake helped to create collective meaning, meaning at level five. Listening for meaning not only for the leadership team or their 300 employees, but equally for their customers, their competitors, their suppliers and the market place. Listening for meaning is how you have an impact beyond words. Nell, I’m curious. Where does this leave you now, thinking about level four, unsaid and level five, listening for meaning?

Nell Norman-Nott:

It’s just a marathon really. I sometimes think that it’s a stretch. It’s something that we can all aspire to. Personally, I’m one of the 99.5% of people who’s never run a marathon. I do love running. And I’m certainly in that majority that need to get better at running and also need to get better at my level one and level two listening. Still running my five k down to Tamarama beach along to Bondi and back up to my house.

I’m sure today’s created as many questions for you as it has answers. Going forward, Oscar and I will spend a full episode on each of the five levels of listening. We’ll dedicate an entire episode to analysing and exploring and investigating each level. During each episode, we’ll hear from the experts on the levels of listening.

Christina:

In the fall of 2005, I find myself at The Military World Championship in shooting. I’m in the lead in the final, and I have one shot left to shoot. The targets is 50 metres away, and the 10 is 10.4 millimetres.

Nell Norman-Nott:

Are they linear? Do you progress from one to the next, to the next, to the next, to the next?

Oscar Trimboli:

It’s simultaneous. You will progress at each level independently, but the reality is based on our research, based on my consulting work, based on what you’ve talked about with your own distraction, Nell, if you’ve got a solid platform at level one, the progression that’s linear may happen faster.

Nell Norman-Nott:

So you could be level five listening in one scenario, do you think, and then level two in another?

Oscar Trimboli:

Absolutely, because listening is situational and relational. You’ll listen to your husband differently than you’ll listen to your kids. You’ll listen to your mum differently than you’ll listen to your dad. You’ll listen to your boss differently to the way you listen to peers and other staff members in your organisation. And for most people, you’re going to listen differently in different contexts. When I’m talking to my mum, I will listen completely differently to when I’m talking to Ruby, my five year old granddaughter.

Each episode going forward now is going to provide three simple practical, actionable tips to take you from where you are today to become a more conscious and deeper listener. Thank you to you for listening to this Apple Award winning podcast. As a gift from me and Nell, we’ve created that simple, practical, downloadable document called The Five Myths of Listening. Visit OscarTrimboli.com/listeningmyths to access the download.

Nell Norman-Nott:

And can you give us a quick sneak peek into one of those myths?

Oscar Trimboli:

One of the biggest myths of listening is that you need to focus on the speaker first. The person you need to listen to first is yourself. So when you get to page two of the PDF, you’ll see some great exercises who around how to listen at level one, listening to yourself. Thank you to you for creating The Deep Listening podcast. We can’t exist without you listening. It takes a village to nurture and raise a child into a healthy adult, and it takes this tribe of passionate listeners to create a movement together so that we can create 100 million deep listeners in the world and have an impact beyond words. Thanks for listening.