Apple Award Winning Podcast

How do you create and sustain a good listening habit?

James Clear is a world-leading thinker and New York Times Bestselling author in the field of habits and behaviour change. 10 million people per year visit James Clear’s website and newsletters, and his book Atomic Habits has sold over 1.5 million copies around the world.

James sits down with Oscar to speak about the intersection of habits and listening. Learn about what a habit is made of, and how they work. Listen as James Clear shares how to adopt an identity of a listener with the simple question: ‘What would a good listener do?’

Transcript

Podcast Episode 067: Making a habit of Deep Listening with James Clear

Oscar Trimboli:

I’m curious what frustrates you when other people don’t listen to you.

James Clear:

The first place I thought of it was with the tailor. I am not a tailor. I don’t know how to fix the clothes and the way they need to be fixed that’s why I’m coming to you. But I do have an opinion on what I want it to look like when I’m wearing it. I’m always annoyed when I go to the tailor and I take a piece of clothing to them and there’s like, okay, I know how to fix this. I’m like, okay, I know you do, but can I just at least, even if it’s not going to change what you do, can you just listen to what I want it to look like afterward even if you’ll do the same thing. So yeah, that’s one where I feel it’s mostly about me being heard and less, less even about what you’ll do and whether you’ll change because of it. But just like if I’m going to bring it in and pay you to do this, I want to feel like you at least know what I want done.

Oscar Trimboli:

A really good example of the four villains of listening, that’s the shrewd listener and they already know how to solve your problem before you get the words out of your mouth.

James Clear:

It feels like that. It feels like, okay, you already know what you want to do and you don’t even really care what I have to say about it.

Oscar Trimboli:

What do you struggle with when it comes to your listening?

James Clear:

Sometimes people will say that when someone’s listening they’re not really listening, they’re just thinking about what they want to say next. Right? I don’t think that I have that problem as much. But I do have a problem where I’m hearing what you’re saying, but I really have a contribution that I want to make. So my problem I guess is, butting in that’s probably my biggest listening foul pole. I find that if I think about the inverse, when am I a good listener? It’s almost always when I’m really curious or excited about the topic. Thankfully, I kept fairly wide ranging interests, so I want to just know how things work and that’s usually when I’m at my best, I think as a listener is I’m not even real… I don’t even really have anything to contribute. It’s less about my opinion or my expertise, it’s more just about, I want to learn how it works and that’s when I’m curious enough or fully engaged. I just keep poking and prodding and asking questions. I think that makes people feel like I’m listening and mostly because I am.

Oscar Trimboli:

Deep listening impact beyond words. Hi, I’m Oscar Trimboli and this is the Deep Listening podcast series designed to move you from an unconscious listener to a deep and productive listener. Did you know you spend 55% of your day listening yet only 2% of us have had any listening training whatsoever. Frustration, misunderstanding, wasted time and opportunity along with creating poor relationships are just some of the costs of not listening. Each episode of the series is designed to provide you practical, actionable, and impactful tips to move you through the five levels of listening. So, I invite you to visit Oscartrimboli.com/Facebook to learn about the five levels of listening and how others are making an impact beyond words.

Oscar Trimboli:

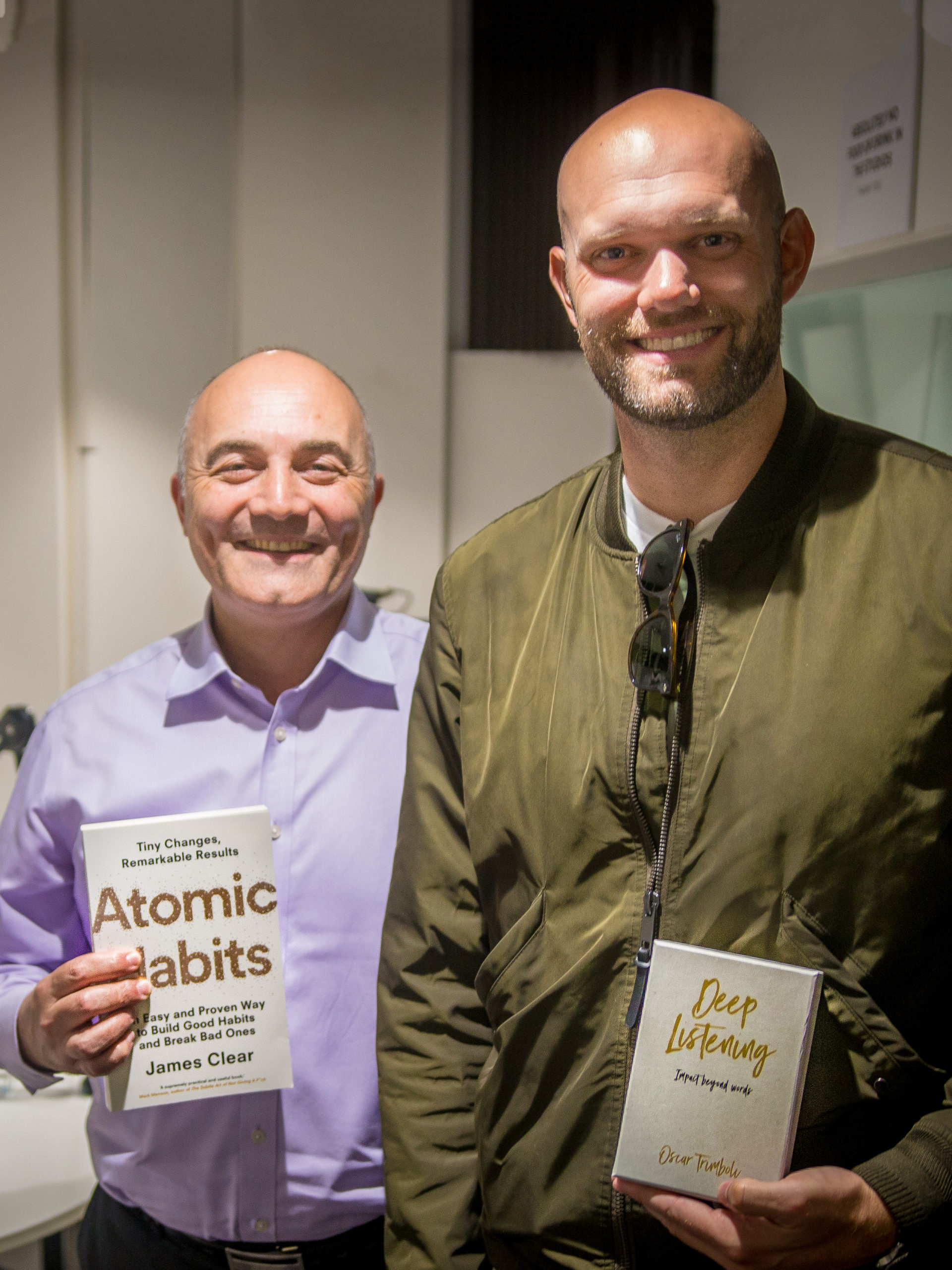

How do you create a great listening habit? How you can learn from the global expert in the area of habit formation. James Clear gets 10 million people per year to visit his websites and newsletters on how to form and sustain habits. His book, Atomic Habits has sold 1.5 million copies worldwide, and it’s fair to say James knows a thing or two when it comes to habits, their formation and how to sustain them. Atomic Habits is not only one of the best research books I’ve read in the last 35 years, it’s also one of the best written books I’ve read in a nonfiction category. James cares and respects the time of his audience. I’ve heard him speak at a book writer’s workshop and he explained that just his blog posts alone can take anywhere between 10 to 40 hours to write, to edit, to rewrite, and then to publish.

Oscar Trimboli:

I’ve been following James’s work for three years and it’s safe to say, I’m a fan and all of my clients who work with me get a copy of James’s book Atomic Habits as part of the programmes I’m part of. The reason I do that is, I haven’t found a better book to explain how to form the habit and how to sustain it. James was kind enough to sign five copies of his book and also signed one of his Habits Journal, so later on we’ll explain how you can access one of the signed copies of the book or possibly even the Habits Journal. One of the most joyful parts of this interview for me was, I was able to do it face to face in Sydney while James was on his Australian book tour. So, let’s learn from James about how to form sustainable listening habits. What’s the cost of not listening as you look at it?

James Clear:

When you’re born, when you’re an infant, you come into the world and you know nothing. You only have the foot in front of your face. So everything that you learn throughout life, everything that is known comes out of the unknown. So it’s the willingness to explore the unknown, to question the unknown, to listen to other people about their experiences and their insights, which are unknown to you. If you’re unwilling to listen, not just in conversation, but even if we use the term like more broadly to listen to what the world is teaching you or to listen to what the environment you’re in is teaching you, then you’re missing insights that are coming. So a lack of willingness to listen is really like a lack of a willingness to learn. So in that sense the cost is very high.

Oscar Trimboli:

Who is the best listener you know?

James Clear:

I feel like there are different listeners in my life that are different, are good in different ways, but I would just say it like a more like a passive listener. They’re good to talk to. They’re good to offload something onto, they’re good at sharing that burden. That’s I feel like a more passive formal listening in the sense that they’re not giving as much to the conversation as much as they’re creating the space for the conversation to happen. Then there are other people in my life who I think are very intensely curious and they’re very good listeners and maybe the ones I even enjoy talking to more because when I do, they poke holes in my arguments or they provoke new insights that I wasn’t thinking about, they give me a different angle or different entry point to think about a topic.

James Clear:

That’s a much more active form of listening for me. It’s like they’re hearing what I’m saying and then they’re immediately going to what about this edge case or what about this insight that maybe you haven’t thought about yet. I tend to find those folks, at least in my life, a lot of them are other writers or other podcasters or content creators, they’re creating or toying with ideas a lot in their own work and so they’re very used to juggling a new idea and seeing how does it float in the air? How does it rotate? What does it look like? I like that active form of listening a lot as well.

Oscar Trimboli:

I’m sure you’re keen to learn how to get a signed copy of James’ book and maybe the Habits Journal. So my request is really simple on social media, whichever one you’re on, share this episode of the podcast, tag me, Oscar Trimboli and tag the full best listeners you know and then go into a draw to win a signed copy of the book. It’s that simple. Share the episode of the podcast, tag me, Oscar Trimboli and then tag the five best listeners you know for a chance to win. Good luck. Coming up next, James is going to explain really elegantly the 125/900 rule. Meaning you speak at 125 words a minute, you think at 900 words per minute, and James is going to explain how the role of an editor can help you listen.

James Clear:

I like that active form of listening a lot as well.

Oscar Trimboli:

Yeah, and we talk about listening being situational and relational. You’ll listen differently to a parent or a policeman, you’ll listen differently to your mother than you will to a child as an example. But as you talked about one example of great listening is the editor’s approach to listening and you’ve worked with editors with your book obviously. What do you think the parallels between an editor and a great listener are when it comes to the creative process typically when you’re listen to resolve, you want to create the spice, but when you listen to create, you need an editor.

James Clear:

That’s an interesting phrase, listening to resolve versus like say listening to explore. The process of editing, that’s an interesting question because I have noticed that for me, writing is like thinking. I often need to write in order to figure out what I think about something and when I’m asked questions that I haven’t been asked before, like this right now, listening is not a topic that I’ve thought deeply about or I’ve written a lot on, we usually when I’m asked a question that I’m answering for the first time, what I find is often what I’m saying, I’m actually talking my feelings. What I mean by that is, I’m talking about how I feel or how it lands with me in that moment and part of this, once I have this realisation, I think maybe we should be much more gracious with people in conversation than what we are.

James Clear:

I don’t know honestly that when I talk my feelings or when I answer a question for the first time, that that’s actually what I really think about it. It’s what I think about it right now or it’s what I think about it for my initial response. But as an example, I had this exercise I went through as a writer where whenever I wrote a new article, I would write at least 25 possible titles to the article. Almost without fail, your first couple of titles are not the ones that you end up choosing. You almost always choose like number 17 or something like that. That makes me think like, what if you were asked the same question 25 times? Almost certainly the answer you give the first time is not your best answer or even maybe your true or genuine or authentic answer, it’s just the first thing that came to mind for you.

James Clear:

So good listeners, if you’re an editor in that conversation, I wonder if they’re good at like teasing that out a little bit more, getting you to brainstorm alternative answers to the question than maybe what you gave the first time. I think with writing, this is perhaps an advantage that writing has over conversation, which is we tend to prioritise whatever the first draught is that comes out of your mouth in conversations like, well, you just said that that must be what you believe. But with writing it’s very much the opposite, we deprioritize the first draught, we say, oh, just get it out. It’s just a first draught. You can edit it later.

James Clear:

That’s I think an advantage that writing has, at least for me sometimes is that my first draught is rarely what I truly think about something and I need a good editor to revise and massage and it’s actually, the real writing is actually the rewriting. But we never treat it that way in conversation, we treat it as whatever you said is what you believe. So I wonder if good editorial listeners are better at the rewriting of your verbal answers.

Oscar Trimboli:

The neuroscience tells us 900 words per minute you can think at and 125 you can speak. So the likelihood that the first thing out of your mouth is what you mean? 11% chance. Can you put yourself in a situation where your editor has listened to you and it’s helped you to explore this book specifically in a different way?

James Clear:

Well there were I think over 800 edits on the finished, this is not the first draught, this is, I’ve probably read it 20 times and then before I handed the full thing to the editor. Even that, I think there were over 800 edits on the first manuscript that they handed back to me. Some of those are small line edits, a comma or delete a sentence or whatever, but some of them are bigger questions, about should this be in there or not? We have a whole chapter that got cut from the book. There were many, many dozens of areas where I think the book was improved because of that.

James Clear:

The ones that actually, that I think of right now that struck me as like, that was really helpful and I didn’t think about it that way, it was more of specific examples like, okay, I get the concept that you laid out, like why it’s important to start with a small habit or I get what you’re saying here about how habits and identity are connected, but this example that you’re giving doesn’t feel like that fully delivers the weight of the big concept. This is one thing that I’ve heard from a lot of readers since Atomic Habits has come out, is that they really like a lot of the examples. It’s the granularity of the detail of how to implement the ideas that makes it really useful. I think a lot of that credit goes to the editor for doing a great job or in my case, the editorial team.

Oscar Trimboli:

Great listeners can be editors. They can help you focus your thoughts. I wonder who the best listeners are you know who can help you to focus your thoughts and your ideas. James in the book, Atomic Habits are the smallest most elemental parts of habit formation and with everyone listening, 86% of us are struggling with distraction. That’s the number one thing that gets in the way of us listening. If you were to help us to adopt an identity of a deep listener, what will be some of the habits we need to consider in that journey?

James Clear:

I talk about in the book this concept of identity based habits of building the habit that reinforces the type of person you want to become. One of the women that is a reader of mine and I talked to as I was working on the book, she lost a lot of weight and she had this really great question that she carried around with her and I think questions are often more useful than advice in the sense that advice is very context dependent. It’s like, oh, it works in this situation, but what if you find yourself in a different situation now it doesn’t apply as much. The question that she carried around with her was what would a healthy person do? So, she could go from context to context and have that question to reinforce the identity. That’s actually in many ways more useful than having a good workout programme or a good diet plan because that you can only do once, but no matter where you’re at, you can ask what would a healthy person do?

James Clear:

Your question, I think is maybe a listening example of that. It’s like you can carry a question around with you, like what would a good listener do? What would a deep listener do? Whether you’re at a cocktail party or at a wedding, or in the workplace and at a meeting, fielding a phone call, whatever it is, you can ask that questioning and pull that out and figure out what a reasonable response might be in that context. Second question that you could ask is like, what am I optimising for? Different people optimise for different things. Sometimes people optimise for money, sometimes they optimise for time, sometimes they optimise for family and relationships, but figuring out what you’re trying to optimise for as a listener and also maybe in a broader, like more meta context, where does deep listening fit into your life in general?

James Clear:

Like what role do you want it to play? What are you trying to optimise for as a listener, where do you… why are you trying to fit it in to begin with? I think those questions are maybe important questions to start with. Because you’ve got to have a decent idea of what you’re trying to move toward before we can get super granular and chunk it down. But assuming that you’ve done that, assuming that you have some of those answers about what you want to focus on or the type of person you’re trying to become, then we’d start to get to some more detailed examples like what you have of turning the phone under grey scale or putting it into your bag. When I feel like I am a good listener is usually when I’m curious, when I’m genuinely interested in the topic that’s happening.

James Clear:

So that’s another question you can ask yourself like, what would a curious person do? What would a curious person ask about? How can I unearth a little bit more about how this process works? Curiosity is an interesting thing because it may be a personality trait, almost certainly is at least some element of personality trait, but it can also be provoked or build up, fostered in some way. Teachers, when they do this with students, if they’re working on reading level, for example, if you have someone who reads at a second grade reading level, you don’t want to give them a book that’s at a sixth grade reading level because that’s too hard and they get upset and frustrated. But if you give them something that’s at a couple of years below them, well then they get bored. So, you really want to be third grade because now all of a sudden there’s enough challenge that I’m interested, but there’s enough success that I still feel motivated.

Oscar Trimboli:

My request is really simple, share this episode of the podcast on social media. Tag me and tag the four best listeners you know to go into the draw to win a signed copy of the book. It’s that simple. Good luck. In the book you talk about going to the gym and too many people think about what watch they need to buy, what workout gear they need to buy.

James Clear:

Yeah, there’s this guy, Mitch who I wrote about in the book and he ended up losing a lot of weight, a hundred pounds, 40, 50 kilos. When he went to the gym, he had this rule for himself where he wasn’t allowed to stay for longer than five minutes. So, he’d get in the car, drive to the gym, get out, do half an exercise, get back in the car, drive home. It sounds silly, right? It seems ridiculous, it’s like clearly this is not going to get the guy the results that he wants. But if you step back, what you realise is that he was mastering the art of showing up. He was becoming the type of person that went to the gym four days a week, even if it was only for five minutes. I think that’s a much deeper truth about habits that people often overlook, which is that a habit must be established before it can be improved, right?

James Clear:

It has to become the standard in your life before you can optimise it or scale it up into something more, and I don’t know why we do this with our habits, but for whatever reason, we’re often so focused on optimising, we’re so focused on finding the perfect business idea or the best workout programme, the ideal diet plan. We’re so focused on optimising that we don’t give ourselves permission to show up, but if you don’t master the art of showing up, there’s no raw material to work with or there’s nothing to optimise. Can I be a good listener just for 10 seconds, right? But at least I have something to work with then. If I can have 10 focus seconds, then next time I can focus on 12 or 20 or a minute. Most people can do something that small and if you can start to make something that small a habit, well then you can’t deny actually at times I do have the identity of being a good listener. I know I can do it for 10 seconds. There’s undeniable evidence that I can be that person.

Oscar Trimboli:

Too many people I work with want to understand how to manoeuvre skillfully at level five. They want to know the ninja move of listening when they haven’t even established the habit at level one, listening to yourself. So, be like Mitch, going to the gym for five minutes. Master level one before you start to worry about anything else when it comes to listening. Listening to yourself at level one is absolutely key and there’s a very good reason why we dedicated two episodes to level one listening. It’s foundational and it’s essential. So visit episode 53 and 54, Oscartrimboli.com/podcast/053and054. I think that’s what Mitch would do to establish a listening habit. I’ll begin to hear what you think. Send us an email at podcast@oscartrimboli.com and tell us how you’re going listening at level one, listening to yourself.

Oscar Trimboli:

I love you to deconstruct something I do as a habit. If I’m to visit a client of mine, the minute I cross the lobby in a building in the city, that’s a signal for me to put my phone often in my bag. Then I go to the lift and when I’m in the lift, I take three deep breaths. Now, my ears popped up. I was going to the 46 story of a building a couple of weeks ago, so I had to turn right to go to the restroom and do my three breaths and then come back again. But the habit was ingrained and then I went to reception. So when I get to reception, they always offer me refreshments and I always ask for water for my guests and myself. That’s my habit. I’d love to know how people could use that and build on it to be better listeners themselves.

James Clear:

Yeah. Great examples. So the first big picture, here’s the framework. So broadly speaking, I divide a habit into four steps. Those four steps are cue, craving, response and reward. Cue, craving, response, reward. Habits are tied to a particular context. They tend to get associated with a given environment. In your case, the example of walking into the lobby boom cue, that’s the first step. Now the next thing that happens after you experience a cue or notice a cue is your brain makes a prediction and this happens so quickly, so rapidly, so flawlessly that we often don’t even realise it. You walk in, you’re in the lobby, cue and then all of a sudden the craving that you have is, oh, I need to pull my phone out and turn it on silent because I’m about to have a meeting. It’s actually that prediction that turning the phone on silent will be beneficial for me that motivates you to pick up the phone and pull it out.

James Clear:

So that’s the response, step three and then you tap and turn it off, and then the reward is the satisfaction of that craving that came in step two. Your second question was like, okay, how can we build on that? How can we use some of those examples to build better habits? So we have roughly four main ways to build a good habit or to shape a habit. You don’t need all four of these to happen, but the more of them that you have working for you, the better odds there are that the habit is going to stick. So the first thing, if you want to build a good habit, the first thing you need is you want your habits to be obvious. So those cues we mentioned, you want them to be obvious, available, visible, easy to see. If the donut is easy to see on the counter, it’s very likely to get your attention. If it’s tucked away in the pantry or not in the house at all it’s less likely the habit is going to start.

James Clear:

The second thing that you want is you want your habits to be attractive. The more attractive or appealing a habit is, the more likely you are to perform it. The third thing is that you want your habits to be easy. The easier, simpler, more convenient, frictionless a habit is, the more likely it is to occur. The fourth and final thing is you want your habits to be satisfying. The more enjoyable or rewarding or pleasurable a habit is, it’s like a positive signal in your brain that says, hey, this is good. I should repeat this again next time. So those four, what I call the four laws of behaviour change that gives you like a high level view for building a good habit, make it obvious, make it attractive, make it easy, make it satisfying. If you want to break a bad habit, you just invert those four. So rather than making the cues obvious, you’ve got to make them invisible, rather than making it attractive, make it unattractive, make it difficult, make it unsatisfying.

Oscar Trimboli:

Are you ready to start the process of building a listening habit? Then take the 90 day deep listening challenge. If you go to Oscar trimboli.com/90days, that’s the number nine, the number zero and days although some people will debate whether the zero is actually a number so it’s Oscartrimboli.com/90days and you’ll be able to sign up for the 90 day deep listening challenge. Each week for 13 weeks you’ll receive tips, techniques, and exercises to improve your listening. The 13 week challenge will help you create the rights base for you to listen to yourself first before you try and listen to anybody else.

Oscar Trimboli:

It will help you to understand that 125/400 rule and establish and facilitate powerful two way dialogue. It will help you improve meetings at work, conversations, briefings, consultations, so that you can listen in every conversation, just one step more to a little bit more deeply as James would say, what would a good listener do? It will also help explain a little bit more detail on each of the five levels of listening to maximise your impact in those conversations every day. So take the 90 day deep listening challenge, visit Oscartrimboli.com/90days. You would see many contexts as you travel around the world and thinking about habit formation across different cultures and across different age groups, are there any significant variations?

James Clear:

Yes and no is the answer from a very meta level or a big picture level, the process of how humans learn habits or those four stages that we went through, those are largely going to be the same. But the type of habits or the way that they’re formed, yeah, it can differ. So first on the age aspect, dopamine signalling in the brain does play a key role and when you feel motivated to perform habits and the signalling of a habit, one reason I added the second stage to my four stage model of craving and prediction is because you can actually map this in the brain. Once a habit has been formed, there’s often a spike of dopamine after the cue has been viewed, but before the action. So for example, a cocaine addict will get a spike of dopamine once they see the powder, not after they take a hit, or a gambling addict will have a spike of dopamine when they see the dice, not after they roll them.

James Clear:

So the motivation actually rises after the cue has come but before the action has occurred. So there’s the cue, then there’s the craving or the motivation, then there’s the action. So dopamine is a key element that motivates us to perform a habit. The reason I bring that up is that dopamine levels, natural dopamine levels change as we age. Actually one of the most interesting examples I came across in the research is that some addicts will actually age themselves out of their addiction because as they get older, once they hit 45, 50, 55, 60, their dopamine levels start to decline and as dopamine drops, so does the urge or the craving to do things. So they don’t get the same urge to perform the addictive habit as they did before. So that is definitely a difference, I think among young and old.

James Clear:

Sometimes it works against you, like younger folks may have a higher tendency to fall into addictive behaviours, whereas you’re less likely to maybe pick up an addiction later in life. But other times it may work for you in the sense that it might be a little bit easier for someone who is say 45 or 50 to remain focused because they’ll feel less of, this is also something that’s been shown with the dopamine research, there’s less of a craving for novelty. As you age, you start to become more comfortable with what you have and where you’re at. Whereas like a 20 year old may have like a great sense of wanderlust and want to… and is always being pulled in a bunch of different directions. So, there are some biological differences there, but I think the cultural differences are actually more interesting.

James Clear:

I think I underappreciated this when I was writing Atomic Habits. So I wrote a chapter about the influence of friends and family on your habits and I knew it was an important topic, I wrote a chapter on it, but I think even since the book has come out, I think it’s an even bigger issue than I realised, which is the power of the social environment on your habits and behaviours. So culturally this plays a really big role. We are all part of multiple tribes. Sometimes the tribes are big, like what it means to be Australian or what it means to be American. Sometimes the tribes are small, like what it means to be a neighbour on your street or a member of the local CrossFit gym or a volunteer at the local school, but all of those tribes, large and small, have a set of shared expectations a set of… a shared culture for what is normal to do in that group.

James Clear:

When habits go with the grain of the cultural expectation, they’re very attractive to do because they are a signal that you fit in, they are a signal you belong. But when they go against the grain, they’re very unattractive. Most people, if they have to choose between, do I get to have the habits that I want but I don’t fit in, I get cast out then go against the grain of the group or do I have habits that I don’t want or don’t really love but I get to fit in. Most people would rather be wrong with the crowd than right and by themselves. Most people would rather… the desire to belong overpowers the desire to improve. So in that sense, I think the cultural elements of habits and behaviour, both culture in a big picture like nations and ethnicities and culture in a small picture, your yoga studio has… exerts a very strong force on what habits we stick with in the long run.

Oscar Trimboli:

Does your manager, your team, your work place value listening? Are you part of the listening community? Norming your behaviour when it comes to listening is one of the reasons why nearly a year and a half ago as I read James’s book, we created the deep listening community as he explained community play such a vital role in helping everybody step up to common behaviours, behaviours that are about improvement every day rather than about huge changes. So if you visit Oscartrimboli.com/community to listen to others, you’ll learn about what they’re doing well, but also you’ll learn what they’re struggling with as well. We’re able to help each other out in that community. It’s a great place to learn to improve your listening, Oscartrimboli.com/community.

Oscar Trimboli:

What you’re about to hear next is actually a question from me. I’m role modelling level four listening, I’ve been so intently listening to James during this interview and it’s great because it’s face to face and you can hear some of my background, verbal affirmations is like mm-hmm (affirmative). So what you’re about to hear is a level four question from me on listening for what’s unsaid. I’m glad I asked the question because it unlocks one of the most important insights from our discussion and the role that genetics plays in listening. My favourite quote is, your genes don’t tell you not to work hard, they just tell you where to work hard. If you were sitting where I am and you had to ask a question I haven’t about the intersection of habits and listening.

James Clear:

One question that I don’t know the answer to but I’d be really fascinated to learn more about is, what…? So I have a chapter in the book about what I call the truth about talent and it’s about the influence that genes have on your behaviour. I think it’s much more… we have genetic inclinations, things that we tend to be good at. Some people are good at one thing, some people are good at something else and so your genes don’t tell you not to work hard, they tell you where to work hard. Specifically, how do your genes influence your ability to listen or your capacity to be curious or your capacity to be emotional in conversation? A lot of times when we get emotional, we become poor listeners. So, I’m curious about the elements that might be involved there.

James Clear:

The most robust or accepted analysis of personality is what’s called the big five and it maps personality under five spectrums. The one that most people are familiar with is introversion on one side and extroversion on the other. But there are other spectrums too, like agreeableness. So people who are high in agreeableness tend to be warm and kind and considerate. You can imagine if someone is say high in agreeableness and maybe high in extroversion, they might be genetically or personality inclined to be able to build habits like writing thank you cards or organising friend groups and getting people together to go out for a party or for lunch or something. I wonder about those different personality traits and how they might influence our ability to build a listening habit and how they influence our ability to stick to listening habits or perhaps most importantly or most relevantly what strategies we should use, right?

James Clear:

So, there’s another spectrum called conscientiousness. If you’re high in conscientiousness, you tend to be orderly and organised. Well, someone who is say low in conscientiousness who might be more spontaneous or disorganised, they could really benefit from some of the ideas in Atomic Habits around environment design because they’re not the type of person that’s naturally going to remember to do it because they’re not an organised type. There are more spontaneous type. So working or living in an organised environment could be really helpful for them to remind them of what to do. Doesn’t tell you that habit isn’t important, it tells you what strategy might be useful for you. I wonder if there’s some like interesting things to unearth with listeners there where it’s like someone who is low in agreeableness maybe would be more confrontational in conversation and maybe that comes across as not as good of a listener. So, do they need different strategies than someone who is high in agreeableness? I don’t know the answers, but I feel like that line of questioning could yield some interesting insights.

Oscar Trimboli:

What it did prompt though is one of the exercises I give to a lot of the people that I work with in corporations is for two weeks listen to a radio station, a podcast or a TV station or read something you completely disagree with and notice your reaction. Every time we sit down and do the debrief from the exercise, people just go, wow, I found out so much faster where my listening blind spots are by listening to people I fiercely disagree with. It came about because somebody challenged me when they said, you keep saying listening is the willingness to have your mind changed Oscar, so when was the last time you had your mind changed and from that they sent me the challenge to listen to people I disagreed with.

James Clear:

My wife has a good question that I like, which is when you do that exercise and you listen to someone you disagree with or just find yourself in that situation, the question is why is this threatening to me? Just answering that in an honest, fruitful way reveals a lot about yourself, maybe it’s positive, maybe it’s negative but learning why you feel so threatened sometimes about things that are not actually threatening or don’t need to be. But it tells you a lot about your initial response, I think raises self-awareness. I like that. I like that exercise.

James Clear:

There are a lot of things that are like this. The tricky piece I think for this one so broadly speaking we could put habits into habits of action and habits of thought. Most of what I write about in the book is about habits of action. Habits of thought are so hard because they are like instantaneous, right? They’re so quick. We just jump to a reaction, we don’t think about it. I’ve been thinking more about how to change that. One example that I have, I think what you need, I think a good way to implant this in your clients or your listener or your reader’s mind, what would a healthy person do, but what you need it’s a different narrative to pull out.

Oscar Trimboli:

Habits of action or habits of thought? I wonder which one you think listening is. Is it a habit of action or is that a habit of thought. I think it’s actually both. Because the difference between hearing and listening is taking action, yet the majority of their time, 80% it will be a habit of thought. So to help you along on that journey, we’ve built the 90 day deep listening challenge to help you move along that journey. To be a better listener every day, visit Oscartrimboli.com/90days, nine, zero, days and each week we’ll give you for the next 13 weeks, a bunch of tips, some techniques, and some exercises to improve your listening. It will help you focus on the most important level, level one, and listening to yourself because you can’t really listen to anybody until you’ve made a space in your own mind before you can listen to the speaker. So take the 90 day challenge, visit Oscartrimboli.com/90days, nine, zero, days and I’m sure like Mitch, you’ll become a better listener every day.

James Clear:

So the example I think of is Mr. Rogers the… it’s a very famous TV show in the United States. Are you familiar? Do you know? Okay. So anyway, it’s like a… it’s something that kids would listen to. But anyway, he’s loved and revered in the United States. When he was a kid, he would watch the news and he would see about a war or a protest or some negative news story that was going on and he would always feel very sad about it. But his mom would always tell him, look for the helpers. Like no matter what is going on poorly, you always find people who are helping. So, what that little story gave him was a way to invert, anytime he saw a negative story, he would just look for the people who were helping and so suddenly had something new to look for.

James Clear:

So, the reason I’m bringing that up is that in this case you’re talking about how do I get people to use this exercise? Well, usually when they’re in a conversation or they’re watching a news story or something, they default to whatever their typical pattern is, but they need a new story or a new thing to pull out like that. Like, look for the helpers. There’s a book called The Outsiders and it talks about these eight CEOs that were some of the top performing CEOs in the last century. There’s one story, about this guy named John Malone who worked as a Cable Executive and he went into this little cable station in Buffalo, New York, it was his first job in the company, and over the course of the next 30 years, he would rise through ranks and eventually become the CEO.

James Clear:

But when he took over this little station, one of his first tasks when he was there they said, we need to paint the building, it’s due to be updated. He said, only paint the side that faces the street. That story, it followed him for the next 30 years, which is cost-cutting was one of his big initiatives. So every time they had a budgeting meeting, every time there was a decision being made by somebody lower on the ladder, they would say, we really care about cost… how much do we care about it? So much that we’ll only paint the side of the building that faces the street. But it gave them a new story to tell. Similar to that, look for the helpers thing, a new narrative to pull out whenever the moment of decision was arising.

James Clear:

So I guess what I’m getting at is like coming up with an example like that or a little story that can encapsulate the overall strategy. If you can implant that idea seed in there, then that’s another thought that can arise as quickly as the initial one could and maybe that little one gives them a different way to manage that.

Oscar Trimboli:

I wonder what the story is you need to tell yourself about being a better listener. Is your story something as simple as that question that James asked, what would a good listener do right now or what would a deep listener do? What do you need to do to make change atomic, so small and so simple that you make progress every day rather than something that is huge and unattainable? If you are Mitch turning up to the gym every day for five minutes, I wonder what your listening gym would look like. Is it as simple as making sure you focus your eyes on the eyes, nose, and mouth of the speaker to stop you from being distracted? Or is it about joining a community of listeners? There are deep listening community visit Oscartrimboli.com/community and you can learn from other listeners or is it about taking the 90 day deep listening challenge or is it about visiting listeningquiz.com to find out, well, what is your listening barriers?

Oscar Trimboli:

I really created this wide range of resources available to all of us, to all improve our listening. I’m sure you’re keen to learn how to get a signed copy of James’s book and maybe the Habits Journal. So my request is really simple, just share this episode of the podcast, tag me, Oscar Trimboli and four of the best listeners you know to get into the draw to win a signed copy of the book. It’s that simple. Share this episode of the podcast, tag me, Oscar Trimboli, and then tag the four best listeners you know for a chance to win. Good luck and thanks for listening.