Apple Award Winning Podcast

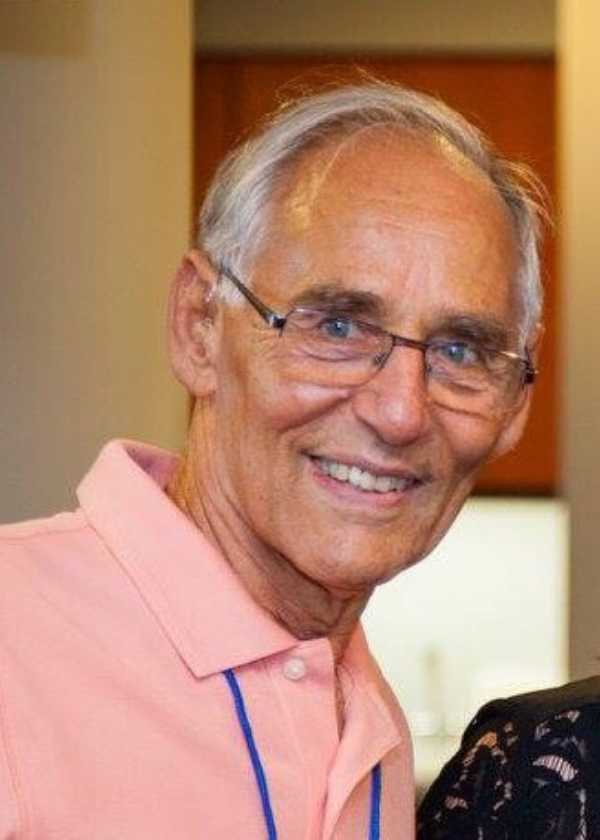

In this episode of Deep Listening we go through the forests of Idaho and the borderland between Canada and the United States as we speak to world class mediator Ken Cloke. He mediates across multiple domains from families, to schools, to corporations. Ken has been a mediator for 37 years, and he is a prolific author with 20 published books.

Ken takes us on a journey that describes the power and the transformational impact of listening for meaning. He finds a way to listen to himself first before listening to the meaning of the conflict. Ken shares how he mediates to prepare for conflict resolution, and how he is present for the meeting. He also shares how to avoid destructive circles and conflict resolution techniques as they apply to the five levels of listening.

Today’s Topics:

- Listening inside yourself to understand the meaning of the conflict.

- The two levels of mediation the issues and the relationships.

- Approaching a conflict with the right attitude. Mediation is a great way to prepare.

- Fully showing up with the realization that the conversation is important.

- Diverting negativity from overwhelming the ego and changing statements to requests.

- Ken shares an example of a couple’s experience and how he goes inside himself to find questions to get to answers.

- How if there is not an equals sign between the heat of the argument and the topic of the argument there is an underlying meaning.

- A touching story of how Ken discovered the root cause of an issue with a teacher conflict and found a way for the teacher to feel appreciated and keep her job.

- Group communication and bringing the human dimension into the conversation and having a transformational impact.

Links and Resources:

Transcript

Episode 007: Listen like a mediator – World class mediator and author of 37 books on the topic of resolving conflict Ken Cloke explores the 5 levels of listening

Oscar Trimboli:

Deep Listening, Impact beyond words.

Ken Cloke:

In order to make room for empathy, for the ability to really listen to someone else, it’s necessary to create a kind of emptiness inside yourself, because if you’re filled to the brim, there isn’t much room for anything else.

Oscar Trimboli:

In this episode of Deep Listening, Impact beyond words, we go through the forests of Idaho, the borderland between Canada and the United States. We speak to world class mediator, Ken Cloke. He mediates across multiple domains, with families, in schools, as part of the legal process and also in working with corporations. A prolific author, his body of work spans over 20 books and his work has continued for 37 years. He takes us on a journey that describes the power and the transformational impact of listening for meaning. Listen for the story about the city that is struggling with a decision to fill up a river and put in a dam.

Listen how Ken draws the two protagonists into a dialogue focused on the meaning and the transformational impact of that.

Let’s listen to Ken.

Oscar Trimboli:

So Ken, when we think about listening through five levels, listen to yourself, listen to content, listen to context, listen to what’s unsaid and ultimately, listen for meaning, I’d love to have a chat to you today through the ones you feel most connected with and the ones you think you can impact the audience on. Is there a place you’d love to start with that?

Ken Cloke:

They’re all important. My work is mostly in conflict resolution, but in order to discover what the conflict means to someone, I have to find it inside myself, and if I haven’t listened correctly, I won’t be able to hear what they’re actually trying to tell me. Because they’re not giving direct instructions on how to get to the place where they’re miserable. The instructions are indirect, they’re metaphoric. They’re about the meaning of the things that have happened to them rather than the things themselves. So, it’s necessary to begin by listening inside yourself and then of course, ultimately what we are doing finally, is listening for the meaning of that event to the person who’s described it.

Oscar Trimboli:

How do you actually prepare yourself physically, mentally and with your presence to be able to listen to yourself first before you connect into the counter parties? Do you have a process that you go through yourself?

Ken Cloke:

Yes, I do. To begin with, I think it’s important to say that there are two levels that you can think of mediations as taking place on. First there is the level of the issues that people are presenting to you. But truthfully, that’s relatively simple and susceptible to technique. But in a deeper level, what happens is the mediation becomes the relationship and the conversation that takes place between the two of them with you being present. Meaning at some deep level, you are the technique. So, it’s necessary to prepare oneself to approach the conflict with the right attitude, if you will.

The way that I personally do this is first of all, to mediate for an hour at least every morning. Then I try to find time to mediate just before going into the session, the mediation session. That is to centre myself inside myself, to close my eyes, to relax, to let go of everything that I can let go of, including whatever impressions I may have of the two of them. Whatever goals I may have for the conversation. Whatever the issues may have been that they presented to me. Because none of that matters until the conversation begins, at which point, it all gets redefined.

What I then do is I simply become present when I greet them. I’m okay with their having conflict with each other, I’m actually quite optimistic about the possibility of our having a useful conversation about whatever it is that we’re doing. But if I instead enter with the idea of solving this problem, or fixing this conflict, making it go away, making it better, what will happen is that I will become invested myself in a kind of place where their conversation is stuck, a kind of knot in their conversation, in their relationship. I’ll get stuck there too. But if instead, I approach it in an exploratory fashion and realise that this conversation is so important that my life could change as a result of what I am about to hear. And if I show up fully with that realisation, then I listen differently, I hear different things, they say things differently. The listener helps to create the storyteller.

Oscar Trimboli:

Ken, if we explore the second level, which is content, and you talked about the role of language there, something that tends to distinguish deep listeners from other is the lens they put on language. So, as you’re listening for language, whether that’s in written form or during the mediation process that you’re part of, what’s the lens you’re looking through for language?

Ken Cloke:

When two people are having an argument, often times, the very first word that they will use with each other is the word “you.” As in you did this, or you are such and such, or whatever it might happen to be. If we take a look at the word you, in connection with something negative, we can see first of all, the word “you” is a pronoun. And when it’s used in connection with something negative, the form of that pronoun is an accusation. In response to any accusation, the two automatic human responses, wherever you go on the globe are number one, denial, and number two, counter accusation. “No, I’m not.” “No, I didn’t,” and you did something else. The object of this is very, very simply, to divert the negativity and all of those negative emotions including the internal negative emotions of guilt from overwhelming the ego.

The person, basically, is just saying, “I can’t handle this attack in any intelligent way.” So, what happens is the whole conversation begins to turn in a destructive circle. And as soon as the person hears it as a statement of fact, like for example, the phrases, “You always” or “You never,” their automatic response will be, “No, I don’t,” or “Yes, I do.” But that isn’t what we were trying to communicate. When we use the words “You always,” or “You never,” what we’re trying to communicate is I’m getting upset here. And this is happening too often for me. So really the two statements are number one, “This is happening too often for me,” and number two, “This is really ticking me off. I’m getting upset here and I’m going to attach and emotional marker to this communication by exaggerating how often you do it, and presenting that as a fact so that you will hear how upset I am and then begin to listen to me.”

All of these statements really, are requests. They’re requests for listening. They’re requests for cooperation. The very first technique, I would say, in listening to conflict conversation is to realise that all of the things that people are saying to each other are presented as declarations, as statements of facts, but they’re actually requests for changes in behaviour. And if they’re presented that way, they become much more acceptable to the person on the other side.

Ken Cloke:

Here’s an example, and it’s an example that takes the whole thing even deeper than what I’ve described. A couple comes to see me and we spend a couple of hours together and it’s very useful, and they walk away and they feel good about the conversation we just had. So, they come back a week later and I say to them, “How has it been this last week?” And he says great, and she says, “Awful.” Well, awful trumps great so you can’t say what was great about it, you have to go instead and say, “Okay, what was awful?” She says, “Well, just this morning, as we’re leaving the house, he left his dirty dish in the sink.” And he rolls his eyes and go, has a huge sigh and says, “I can’t believe you’re bigging that up.” And she says, “Well, that’s just like you to pay no attention to what I want and to the things that I object to.” And now they’re off and running. So, the argument goes on and on.

Here’s the basic situation. They’re getting in to this huge argument and the emotions are getting very hot, and the thing that they’re arguing about is a dirty dish in the sink. And those two things don’t match. If they don’t match, in other words, if you can’t make an equal sign between them, it means there’s something else other than just the dirty dish in the sink. And the other thing that there is is the meaning of the dirty dish in the sink. So, I say to her after they’ve argued a little bit, “What did it mean to you that he left his dirty dish in the sink?” She said, “It means he doesn’t respect me.” Okay, now that’s significantly more important. You can understand why somebody would get upset not so much about a dish, but about respect. But this even doesn’t go quite deep enough, because I can tell from their argument that this has touched a deep place inside of her. She’s really upset about this and he doesn’t get it. So, I say to her, “What does it mean to you that he doesn’t respect you.” And she says, “It means he doesn’t love me.”

Okay, now we’ve got it. The dirty dish in the sink doesn’t just mean the dirty dish, it means he doesn’t respect her and because he doesn’t respect her, it means he must not love her. Now his mouth drops open because he can’t believe that we’ve gone from this dirty dish to the fact that he doesn’t love her. So, he’s kind of stunned and I turned to him and I say, “Is that, right? Is she right? Do you not love her?” The reason I say that is because she’s taken him to an existential place. A place which means everything for their relationship. Maybe he doesn’t love her. And maybe that is the truth, and that is what’s going on. But if that is the truth, I have to give him permission to say that because if I don’t, she won’t believe what his answer is. So, I say, “Is that true?” And he says, “No, it isn’t true.” So, I say, “Tell her whether you love her or not.” He turns to her and he says, “I do love you and I do respect you, and I’m sorry about the dirty dish in the sink.” So now he’s apologising for what happened.

But even this isn’t quite so simple. Because this is a relationship. And in every conflict and in every communication, it goes in both directions. So, there’s a piece for her in this. And I have to figure out now what is the piece for her? And I find this, of course, through exercising empathy. I go inside myself and I ask myself why would I get so upset about a dirty dish in a sink? And I come back with a question based on what I come up with inside myself and my question is this: “What is going to happen to the dirty dish in the sink? Sooner or later, what’s going to happen?” And she says, “I’m going to wash it.” I say, “Why?” She says, “Because that’s what I’m supposed to do. That’s my role, is to keep the house clean and to wash those dishes,” and I said, “Who says?” And she says, “I say.” I said, “Where did that message come from?”

And now we’re beginning to see that the reason that she feels he doesn’t respect her, is not just because there’s a dirty dish in the sink but because placing it there means she has to wash it. And that’s an assumption that she has made herself. It’s an expectation of herself. That comes from her mother, and her mother’s mother and her mother’s mother before her. And it’s something that has not been negotiated, has not even been discussed between the two of them. So, I turned to him and I say, “Are there things like that for you that you believe are your responsibility, that you’re supposed to take care of?” He says, “Yeah.” Now he can see the picture, finally. And taking care of the yard, fixing things around the house. And I say, “Do you ever feel that she doesn’t respect you sometimes when she doesn’t handle those things correctly? When she creates more work for you?” Now he gets it. “What is one thing she could do that would make your work easier for you?”

Then I turned to her and I say, “What is one thing he could do that would make your work easier for you?” Now they’re beginning to talk and they reach agreements with each other, then they have to actually of course, fulfill those agreements. But because it’s mutual, because it isn’t just him who screwed up, because it goes deeper than that, and it really opens up a place in their relationship that is on the one hand fundamental, and on the other hand, not being spoken about. Why? Because it means too much to each of them. Because it’s so deeply connected. Because it manifests itself in small things but in itself is not a small thing. It’s a huge thing. It has to do with identity. With self-image, with expectations.

Oscar Trimboli:

Do you have another example in those environmental or corporate examples?

Ken Cloke:

I did a mediation involving a school teacher who had been the head of the teachers’ union for over 20 years and then had gone back into the classroom as an ordinary teacher. As soon as she went back into the classroom, there began to be problems. Difficulties between her and the kids, lots of yelling at the kids, lots of yelling at her co-workers, other teachers who she had represented for all those years, and those got significantly worse and she began to use not just your average swear words, but your world-class swear words in the presence of the children against her co-workers. So, the principal called me and said, “I’m going to have to fire this woman but I’ve worked with her for all these years and I’m hoping that mediation can do something to allow her to keep her job.”

So, we met together and with her and three other teachers who she’d yelled at in front of the kids and used a lot of profanity. They began to describe what happened and after each description, she said, “No, no, that wasn’t the case. That wasn’t the way it happened. They were the ones who triggered it, they were the ones whose fault it was.” And I sat there listening to this, thinking there’s no way that we’re going to have a useful conversation if this is just accusation and defence. So again, I went inside myself and tried to find the her inside of me and see what would be going on for me. What would have led me to feel this way and to be so angry in this circumstance.

As she was being defensive and describing all of this, I interrupted her in the middle of a sentence and I said, “Excuse me, can I stop you and ask you a question?” She said yes and I said, “Has anyone ever thanked you for what you have done for this school?” And she just burst into tears sobbing uncontrollably, and nobody had ever seen her blink over 20 years. She was the tough one, the negotiator for the union and now here she was, just sobbing completely uncontrollably. As soon as she did that, the other teachers who were there to accuse her were completely shocked. I said, “Okay, we’re going to stop describing the things that she did that were wrong, and instead, I’d like to ask each of the three of you to tell her personally something that she has done for the school that’s made a difference to you and your life, or made a difference to you in terms of your ability to be a teacher.” And they began describing these things, and now they’re all crying.

She immediately admits a hundred percent every single allegation, every accusation, every single thing. She says, “Yes, I did it. I’m so sorry. It’s my fault and I shouldn’t have done it.” The other teachers, hearing this, say, “This isn’t entirely your fault. After over 20 years outside the classroom, you came back to become a teacher and of course, you weren’t prepared to handle this and we weren’t there to support you the way that you had been there to support us before. This is partly our fault because we should have come in and helped you.” So, I say to her, “Does this do it for you? Is this over?” She says, “No.” And I’m immediately worried that maybe we’ve left something out. And she says, “I need to now go to the other teachers and to the parents and the students and apologise for what I did.” The other teachers say, “We’re going with you. And instead of you’re just apologising, let’s talk about what we’ve all learned from this conflict about how we can work together better to make sure that kids get a good education and that we support each other.”

The next thing that they did was they asked the principal to have a staff meeting where everybody showed up and nobody was grading papers and nobody was sleeping. It was the most intense conversation they had ever had.

Oscar Trimboli:

Is there a story you think that would serve our audience about mediation in a corporate context for some work you’ve done that demonstrates how groups need to listen to each other rather than merely individuals?

Ken Cloke:

I was working in a medium-sized city in Arkansas. Members of the city council and the city attorney had called and said, “We’ve got this horrible problem here. Can you come and help?” There’s a dam in the city and the environmental groups want the dam taken down and the city council wants the dam remaining. The environmental groups want a river and the city council people and the corporate world wants the dam because it provides electricity and jobs and a whole series of other things. So, everybody had their reasons for this. We came in and we trained members of the city council, whole bunch of city staff and leaders of the environmental organisations in dialogue techniques. They all got trained in the same techniques. The next day after the training, they had a dialogue about the dam and they had great discussions in the small groups about them.

But the main discussion that I want to mention was one that took place in one of the small groups where the main leader on the city council who favoured the dam was present, and the main leader of the environmental groups that were opposed to the dam was also present. The guy who is opposed to the dam, because of the training, turned to the member of the city council who favoured the dam and said, “I don’t get it. What does this dam mean to you? Why is this so important to you?” He said, “Well, I’ll tell you. My father and I used to go fishing on the dam. I loved that time with my dad. And I go with my son and I loved the time with my son and I’d like to make it

possible for future generations to have that.” And the guy who is the head of the environmental organisation said, “Well, that’s really interesting because my dad and I used to fish on the river. And my son and I fish on the river now and I really love those times too and I want to make it possible for people to fish on the river.” So, what they came up with was a plan where they can have both. But neither one of them had listened to the other one before this.

That’s an example of how bringing the human dimension into the conversation, being human, being real, being authentic, talking about what things mean to you can have a deeply transformational impact.

Oscar Trimboli:

What a beautiful note to finish on and that summarises so well the impact of listening at level 5. Listening for meaning. Because it’s in meaning that we transform the understanding, the dialogue and the impact, not just for the individuals, but in this case, for everybody in the community. Ken, thank you so much for taking us on a marvellous adventure through the mountains of Idaho.

Ken Cloke:

Thank you very much, Oscar. I appreciate it and I appreciate all the work you’re doing to promote this idea. Thank you to all your listeners for tuning in.

Oscar Trimboli:

Did you enjoy listening to the sounds of the Idaho woods as much as I did? Did you notice the cat in the background? Did you hear the creaking of the chair on the wooden floor board while Ken was talking? If you were listening on a different level, you might have heard that. But the level that was most powerful for me was how Ken showed three very distinct examples of listening for meaning and what that creates. How much of your day are you spending listening for meaning? And how much of your day are you thanking others for what they do? Because it was in the story of the union leader returning to work as a teacher in the classroom, that the very simple exploration of what’s unsaid or level 4 listening was highlighted by Ken. I’ll look forward to joining you in our next episode where we listen for something completely different.

Oscar Trimboli:

Deep listening, Impact beyond words.