Apple Award Winning Podcast

Anthony Weeks is an illustrator, documentary filmmaker, and visual storyteller based in San Francisco. He has more than 18 years of experience working with senior-level product and strategy development teams to think visually and turn data into stories.

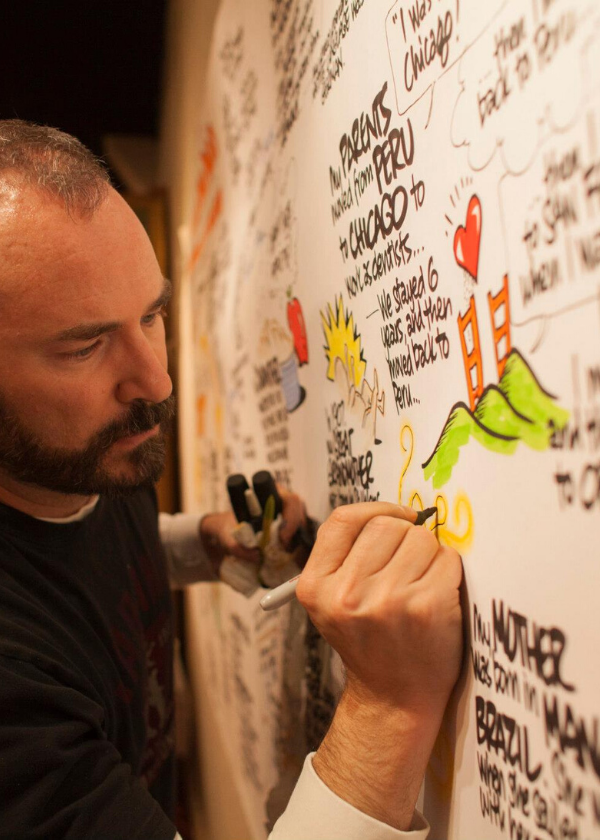

In the role of public listener and illustrator, Anthony collaborates with project teams to create visually rich chronicles and murals of conversations in real time. The visual storytelling facilitates dialogue, engages participation, clarifies vision, and animates the process of ideation.

In this episode, Anthony explains how he prepares to listen and the role of subjectivity in listening. He provides some very practical tips on what to do when you get distracted whilst listening.

Tune in to learn

- Anthony is a graphic facilitator who listens to teams and groups and then creates a visual chronicle of the conversation.

- The role of meaning and how to think about listening in capital letters.

- Listen carefully as he talks about his capital S and the role of subjectivity in listening.

- Explore with him as he talks about the role of silence in a one-on-on dialogue.

- How silence can honor a room in a group context and give the room an opportunity to think and reflect on where they are at.

- His capability to listen for meaning and bring it to life in his visual artifacts.

- Preparing for the day ahead. Anthony has had several repeat clients who know why he is there.

- When working with a client for the first time, he gets in the room early and positions himself so he will be present but not intrusive.

- His role of listening dictates where he sets up his work area. After a brief introduction, he listens and creates drawings.

- Anthony claims his subjectivity as a listener, and he hopes he is hired for that.

- What is not being said can have many meanings, but we aren’t talking about it because of culture, safety, or it’s a painful subject.

- The challenges of getting into the mental and emotional space of listening.

- People talk about mindfulness a lot. For Anthony, mindfulness is meditation everyday, every morning, and before every meeting to create space to listen in a dedicated way.

- Appreciating and honoring the facts that we can all be good listeners.

- An example of listening from the perspective of a 911 operator. Transactional listening and recognizing oneself as a listener.

- The importance of coming up with a language around listening.

Links and Resources:

Transcript

Episode 018: Deep Listening with Anthony Weeks

Oscar Trimboli:

Deep listening, Impact beyond words.

Anthony Weeks:

When we listen and interpret things only through our own listening filters, we’re often going to miss things because we’re going to say, “I don’t understand that, therefore I can’t listen to it because I don’t understand it.” And he taught me that sometimes you really have to work very, very, very hard in order to put those filters aside so that you can let the listening come in and you can hear somebody and hear exactly what they’re saying. And put your own interpretation of it, your own historical context aside to the degree that you’re able in order to hear them.

Oscar Trimboli:

In this episode of Deep Listening: Impact Beyond Words, I have the opportunity to talk to public listener and visual scribe, Anthony Weeks, based in San Francisco in the United States. Listen carefully as he talks about the role of meaning and how the think about listening in capital letters. Listen carefully as he talks about his capital S and the role of subjectivity and listening. Explore with him as he talks about the role of silence in one-on-one dialogue. But more importantly, in a group context and how silence can honour the room and give the room an opportunity to think and reflect on where they’re at rather than just continue to speak.

I think Anthony’s biggest gift is his capability to listen for meaning and to bring that to life in his visual artefacts. Let’s listen to Anthony.

Anthony Weeks:

And I call myself a public listener because I am, and I think you’re familiar with it, I am a graphic facilitator. And so what I do is I work with teens and groups and as they’re talking and having their conversations, I listen to what they’re talking about and on a big canvas a couple metres wide and maybe a metre or so tall, I listen to what they’re talking about and create a visual chronicle of their conversation. And the purpose of it is beyond just visual note taking. It’s more to create an interface for them to see their conversation unfolding in real time as they’re having it.

So using text and colour and graphics, I’m drawing and listening and writing things down and over the course of a day, there emerges this … it looks somewhere between graffiti and comic books if you mesh those things up together. And in the process people are able to see their own word. They’re able to see the words of their colleagues. They’re able to see the connections between the themes and the questions, the ideas that have emerged and it’s hopefully not just data. Hopefully, over a course of a day there’s a story that emerges where they’re able to look back at it and squint and say, “Ah, okay, there’s the stuff that we talked about.” But then there are these connective threads and there’s this tissue that really pulls these ideas together in a way that elevates the conversation beyond just data points.

Oscar Trimboli:

For those in the audience who haven’t participated in a visual scribing activity that you’ve undertaken, maybe in an organisational context, it may be in corporate, it may not be. Just place us in a room, talk us through the day. Talk about how you prepare for the day ahead because it’s a long time to be listening.

Anthony Weeks:

Well, I have some clients that fortunately have been with me for many years, and so when I show up they know me, we exchange pleasantries, they know what my gig is. They know that I’m the drawing guy who is going to be at the side of the room or maybe a little off centre in the front of the room and they know why I’m there. I think the real test is when I am working with a client for the first time. I usually insist on getting into the room about an hour at least ahead of time so that I can set up my space, so that I can get a feel for the room, so that I can position myself to be present but not obtrusive. And I also need to know how do they want me to listen? Do they want me to listen as more of a facilitator? Or do they want me to listen as more of an actively listening scribe? Because that matters where I’m going to be in the room.

So let’s say somebody says, “I just want you to be here because I want you to ‘capture what we say’.” So I’ll say, “Okay.” So I’ll set up on the side of the room. I’ll hang my paper with tape. I will put my art supplies on a table and I will be maybe to the side of the room so that people can see me, and then at the beginning of the meeting, the meeting facilitator will usually, hopefully introduce me and say, “This is Anthony. He’s our graphic facilitator today. If you haven’t seen graphic facilitation before, he’s going to be listening to what we say and he’s going to be creating some drawings of what we talk about.”

So then when they say, “Here’s Anthony. He’s the drawing guy. He’s going to be drawing while we talk.” Occasionally you’ll see some cocked eyebrows like, “What? What’s he going to do? I don’t really get this.” And it’s even worse when people do not introduce me and the conversation starts and I am drawing and people are even more confused about why I’m there. The introduction is pretty necessary.

So let’s say okay we have two hours of conversation. Let’s say we started about eight o’clock in the morning. By ten o’clock we’re ready for a coffee break and people will invariably come up and say, “Wow, this is really cool. This is really great.” Sometimes they’ll say, “You draw really well. I can’t draw. I can only draw stick figures.” But the best compliment is when somebody says, “You really got what we said. You really got what we said.” And they will stand back and they will look at it and they will you can see it in their face that they’re replaying the conversation that they just had for the last two hours and they can see the quotation bubbles. They can see these themes that are written in large font. They can see these little details that might have come out that might have seemed inconsequential at the time.

And I’m not attempting to be this automaton scribe that’s capturing every single word that’s being said. It’s impossible. I will lose every time. Especially if people are presenting power points or other slides. But I do find that when people see their words up on the sheet of paper alongside those that have been spoken by their colleagues, there’s this recognition that what they’ve said is important. It was important enough to be written down. It’s important enough to be part of this whole tapestry that we’re creating. And so there’s a fair amount of responsibility that goes with that.

So over the course of the day I may create anywhere from four to six, maybe even eight of these canvases that include maybe their different points in the conversation, maybe their different themes, maybe their different items on the agenda that deserve specific information, but by the end of the day we’ve covered the walls with these canvases so that people feel like they’re in a story theatre. They’re seeing their whole story around them as they’re having it and a good facilitator will create time in the agenda to take the participants through a gallery walk to look at all of the things that are on the wall and say, “This is your conversation. Yes, it was interpreted by Anthony, but this is your conversation. Take a few minutes. Pick up your notebook. Walk around. Look at what you see and maybe take your own notes about some things that pop out at you.” Maybe it’s even a conversation starter for another agenda item about okay, we have all this information, what do we want to do with it?

And then at the end of the meeting I’ll take those murals away. We will digitise them. We’ll turn them back around to the participants so that they’ll have that experience of the real time visualisation in the room, but then they’ll get the digital images later so that they can refer back to them and then they look at them in two days, two weeks, two months and be able to re-create that conversation in their mind when they’re looking at the graphics.

Oscar Trimboli:

What do you choose to represent? What do you choose to leave out?

Anthony Weeks:

I think one of the things that … I’ve been doing this for about 18 years, and in my 18 years I would say that I’ve come to claim my subjectivity as a listener. Similar to what I was saying before. I think that I claim my subjectivity because this is not an objective record of what’s being said. It’s not something that is set apart from its own biases whether it’s the choice of colour, the choice of font size, the choice of words that I put on the paper, the graphics. And so, I’m hoping that people are hiring me for my subjectivity. They like the way I listen. And so that tends to be the way that I go to the marketplace is just saying, “I’m not claiming that this is the truth, capital T. I’m claiming that this is my best effort to re-create your conversation in a way that’s intelligible, that’s engaging, that’s interesting, that’s authentic, but it’s not necessarily the only truth.”

So, there’s that and then I think that when I’m listening I learned this from somebody who I admire very much in Silicon Valley who’s a cultural anthropologist, and she’s been studying families in Silicon Valley for years and years and years. And she has gone on vacations with them. She’s lived with them. She’s studied them. She’s listened to them. And one of the things I learned from her was how to listen for capital letters. And by that, I mean she listens for those points of inflexion or points of emphasis where if you could visualise it in your mind they would be saying them with capital letters. And so, listening for those capital letters to say, “Ah, that’s it. That’s what they really mean to say.” Or, “that’s important to them.” I’m going to write that in capital letters because that sounds like it’s a big deal.

And I think that sometimes when I’m listening, listening, listening, people will set up something by saying, “So what I really mean to say is.” And that’s just a softball. I mean that’s really easy. Oh, okay. I got that. They’re ready to say something important. But sometimes it’s more subtle. Sometimes it’s more they’ll be saying something and then they’ll sigh and they’ll stop, and they’ll give a moment of silence, and then they’ll say what they really want to say. And so, when you listen for those cues and when you listen for those points of direction where somebody is about to say what’s really important to them, then I think you get a little bit more attuned to listening for the capital letters and listening to the meaning that they’re about to provide you.

Oscar Trimboli:

I heard a lovely capital S subjectivity for you, my friend, as we’re going through this conversation today, it’s been a beautiful thread all the way throughout. For our listeners, one of the things that a lot of people aren’t conscious of is listening to what’s unsaid. As a public listener, how do you become conscious of listening to what’s unsaid?

Anthony Weeks:

Honestly, I don’t think you can avoid it. However, when you’re in the dual responsibility of listening and then putting pieces of information or stories up on a piece of paper, I think you need to tread lightly. I think you need to be careful because what’s not being said can have many, many meanings. Some of it might have to do with we all know that that’s present but we’re not talking about it because of culture. We all know what’s being unsaid, but we’re not talking about it because of power or because of safety. We all know what’s being unsaid, but we’re not talking about it because maybe it’s painful. Maybe it’s something that we’ve had a difficult learning experience and we all know it, but we’re not ready to talk about it yet.

And I think that there’s something about that that is difficult because you don’t want to be ignorant to it. You don’t want to be oblivious, and yet, if you’re not part of the in group and if you don’t know why it’s being unsaid, I think you need to either ask questions about it offline or online depending on the situation. You need to ask other questions that give you some more information. I think that you can represent it in different ways. I’m thinking of one of my interviewees from my listening project is a very successful, very accomplished film editor here in the United States. She lives in New York. And she has edited several different documentaries that deal with some pretty sensitive subject matter.

And so, when we were talking, she was telling me about how the raw material that she has to deal with is really just what people say. It’s the audio that’s on the tape or on the whatever that she has on the media. And she said, “I know what’s not being said, but I can’t necessarily manufacture something that’s not being said, and I can’t put that in there. But, what I can do is I can edit things together not in a way that says something that is no true, but I can create space in between the words. I can put different sentences together in juxtaposition. Which is actually what they said and it’s actually what they meant, but it’s not the way that it came out in the conversation.” And so when she was talking about that editing it was interesting to think about how if we had the power to do so, how would we put peoples words together in a way that demonstrated what they really meant to say.

And so, I think that sometimes when I’m a graphic facilitator, I may write down exactly what they said, and I may include a graphic that may be something very simple. It may be something like grey clouds. I may include something where what they’ve said is set apart spatially from the rest of the conversation because what they said was so singularly important or poignant or interesting or just deserving of its own space that the only way that I can do that without manufacturing something that they didn’t actually say is just to use graphics and use colour and use space in order to give it some prominence of its own.

Oscar Trimboli:

And I’m fortunate enough to be watching Anthony while he’s describing this and there was an absolute shift in his whole-body energy when he described capturing in a different colour and a different graphic. And there was a particular situation he was actually visualising that I think true to and said he couldn’t bring fully to you in the audience the actual emotion that was in the room but that emotion was coming through his body as I was watching him through the interview.

It was fascinating.

Oscar Trimboli:

Anthony, you’re working in two hour blocks of listening, and you’re doing that over a very long day or a very long series of days, and one of the things we love to provide for our audience is some really practical tips. So how do you stay focused when you inevitably will be distracted during this time that you’re capturing what you’re hearing during a two-hour session? I’m curious what tips or techniques you utilise or what tips and techniques you think the audience could use to know when they’re distracted what they could do about it. To become a better listener.

Anthony Weeks:

Some of them are very elementary. Some of them are so simple they’re ridiculous. I think that if you’re going to be a listener, if you’re going to be a dedicated listener, you need to set up the environment so that you can listen. And that includes proximity to the people who are speaking. It includes amplification if necessary. It includes the arrangement of the seating so that people can not only hear each other but that I can hear them as well. If indeed my job is to listen to what they’re saying. Some of it has to do with choosing spaces and environments that are conducive to listening. Places that are not going to be in the way of traffic whether that’s passers-by or other kinds of conversations or meetings that might be distracting. So, there’s this spatial part of it and that’s easy. We can usually deal with that.

The harder part sometimes is getting into the mental and even emotional space of listening. And I think that mindfulness has become kind of cliché. I think that we talk a lot about mindfulness and I think that in here nearby Silicon Valley people talk about mindfulness a lot, but they usually talk about it as, “We instituted a mindfulness programme in our company. We increased our productivity by 75%.” No, that’s not the point.

Oscar Trimboli:

So now make it practical for the audience. How do you do that?

Anthony Weeks:

Mindfulness to me is meditation. I do meditate and I meditate every day. I meditate in the morning. I meditate even before a meeting and sometimes it’s really just about I wouldn’t even say clearing the mind because that’s hard to do. I would say it’s calming the mind. It’s creating space in my instrument. My ears, my brain, my body, to be able to listen, and to be able to do so in a dedicated way so that I’m not thinking about the current state of the world. I’m not thinking about a difficult conversation I may have had with my partner. I’m not thinking about my grocery list. I’m really focused on this is my job. My job right now is to listen.

And to even say that to myself over and over again as I’m at the wall, my job is to listen, my job is to listen. And I think that sometimes that’s really helpful because it’s mantras and repetition and these kinds of personal exhortations sometimes are meditative in and of themselves. And so saying things like that before I’m ready to start as I’m working in the even that sometimes the conversation may not be all that scintillating. And so, I just need to remind myself, my job is to listen.

So, there’s the mindfulness and the meditation part. I think there’s a part of it too, which is being intentional about listening and that goes with the mantra of my job here is to listen, but more and more as I talk to other people about listening, listening is not just something that happens. It’s not just something that we do by accident. Listening is an intention. Listening is a skill. Listening is a competency. Listening is something that we need to work at. And unless we’re conscious of that, then it’s probably not going to happen in the ways that we hope or the ways that are needed. And so I think that there is a part of it where practising listening starts with the intention that you’re going to listen and the intention that you’re going to be in service as a listener.

And some of us may have a longer way to go in order to do that well. Whatever that means, but I think it needs to start with the intention.

Oscar Trimboli:

For clients I work with, just noticing they’re distracted is difficult for them. So imagine you’re 90 minutes in, it’s the afternoon session and you’ve still got half an hour to go, and you may notice you’re distracted and drifting off, or you may not. How do you even notice, Anthony, when you’re being distracted from listening in those settings? Or maybe not even in those settings?

Anthony Weeks:

Some of it has to do with energy. I think that my energy starts to flag when I’m having a hard time staying present as a listener. I find it difficult to track. I find it difficult to hear what people are saying. I find it to be honest I find it irritating. When I find myself getting irritable about having to listen then it’s like, what’s getting in the way here? Why am I getting so irritated with listening to this group? Is it because they’re not saying something interesting? Or they’re repeating themselves? Or they’re talking about things that are off topic? But continuing to monitor my own ability to listen is part of it.

If I’m in the responsibility of not only being the graphic facilitator but also having an opportunity to interact with the group, I think that I might call it out. I might just say, “You know what, I am having a hard time listening to you right now. How are you feeling? How’s it going for you? Because I’m having a hard time listening because it seems like we’re scattered all over the place and we’re not coalescing. Or we don’t have the same energy right now that we might’ve had at ten o’clock this morning. So, do we need to take a break? Do we need to re-calibrate? Do we need to just take a moment to figure out what we’re supposed to be doing here?” But I think that paying attention to that energy and paying attention to that emotional connection with what you’re hearing and what you’re listening to or listening for is an important barometer of how are we doing as listeners here.

And being able to be humble enough to say, “I’m having a hard time listening, what about you?”

Oscar Trimboli:

Which brings us to the role of silence in listening. Or the absence of words. How deliberate are you in creating and amplifying silence when you’re listening?

Anthony Weeks:

As a graphic facilitator, I love it because it gives me a chance to catch up. It gives me a chance to listen to what I’ve been listening to. It gives me a chance to stand back and look at what I’ve done thus far and say, “Oh, there’s also this, this, and this that I haven’t written down yet. Or there’s this, this, and this that somehow needs to be tied together.” I think for groups silence gets short shrift because silence is viewed as uncomfortable. It’s viewed as not knowing. It’s viewed as wasted time.

And so, making the space for silence so that it is part of the work, it’s part of the reflection, I think is so important. Because if you’re just talking, talking, talking then you’re privileging talking about the listening. You’re privileging talking to the exclusion of listening sometimes. And so making space for silence gives you a chance to reflect, but it’s also a little bit of a, for lack of better word, a brain cleanse so that you can re-enter the conversation as a listener and you can re-enter the conversation as somebody who is present as opposed to, oh, I’m getting ready to say my next piece. And I’m getting ready to rebut or respond to what you just said.

The silence gives us some space to understand and comprehend and to be present that doesn’t happen when we’re just talking, talking, talking.

Oscar Trimboli:

Is there anything that we missed that you think will make an impact for the audience?

Anthony Weeks:

I guess one of my favourite anecdotes thus far from the research I’ve been doing talking to different listeners is really to appreciate and to honour the fact that we all can be good listeners. And I think that that was illustrated best by an interview that I did with somebody who is here in the States we call it 911, it’s the emergency response. So he is an emergency dispatcher, and I tried and tried and tried to get an interview with him. We had multiple text and email exchanges and every time I asked him, “Hey, can I have an interview with you?” He would say, “Ugh, why do you want an interview with me? I’m not a good listener. Why do you want to interview me? I’m not a good listener? Ask my wife. My wife would tell you I’m not a good listener.”

So, I persisted. I persisted. I persisted. And finally, he relented and gave me an interview and was cranky about it the whole time and I just asked him, I just said, “You know, okay, let’s put all this other stuff aside. I know you say you’re not a good listener. I know your wife doesn’t think you’re a good listener according to you. That’s well and good. Tell me how you listen as a 911 dispatcher.” So he told me about how he listens to the tone of their voice. He listens to the callers’ description of what’s around them. He asks them questions about who’s nearby, if anybody.

He listens to them about time. What’s the chronology of events? How did things happen to where you got to the point where you called me. What are you experiencing right now? What are you seeing? What are you feeling? What are you hearing? So we talked about this for several minutes and I didn’t want to put words into his mouth, but at some point I just blurted out, “It sounds like you’re a really good transactional listener. You listen for information so that you can do something with it and take action.” And there was some silence, and there was a pause, and you could almost hear him getting a little puffed up with pride over the phone.

And he said, “Yeah, I guess so. I’m a transactional listener.” And I think it was probably the first time he had ever used those words, but I think what happened in that moment was he recognised himself as a listener, whereas he hadn’t before. And there was something about giving language to it and giving vocabulary to it that gave him something to hang on to. To say, “Yes, I’m a listener, and even if I need to do some work with my wife to be a better listener to her.” And we didn’t get into that, there was something about giving him something to attach to his particular skill in listening that was valuable. And I think that in my research, and I’m assuming in yours too, Oscar, there’s something about coming up with a language around listening that’s really important. It’s not just about we’re good listeners or we’re not. Or we listen, or we don’t. We listen in very different ways. And that doesn’t get us off the hook for becoming better listeners in other ways.

I mean, if I’m a great transactional listener, but I’m not a great listener in my intimate relationship, then yes, I have work to do. Likewise, if I’m a psychotherapist and I’m an empathic listener and I am able to just hold that space for somebody else that’s great. And yet, if that means that I don’t listen well when somebody is telling me something in detail that I need to pay attention to, then yes, perhaps I need to become a little bit more of a detail listener or a tactical listener so that I’m able to listen in that way too. And so there are all these different styles and ways and methods of listening that yes, we can be proud of and we can embrace and we can amplify so that we all learn to listen in the best ways we know how.

And we can also aspire to listen in ways that we don’t know how.

Oscar Trimboli:

Thank you for your time.

Anthony Weeks:

It was my pleasure. Thank you so much, Oscar, for having me. It was delightful and you’re in Australia. I’m here in the States, but I think that we made a good connection today and I appreciate it.

Oscar Trimboli:

Anthony’s ability to talk about listening through a range of types and language sets is quite extraordinary. I love the way he prepared the scribing and the way he talked about preparing himself for listening. It was a really good example of listening to yourself or level one listening in preparing really deeply. I’m sure like me in listening to Anthony the palette of language that he uses to describe listening is quite extraordinary. Whether it’s an opera singer, a migrant, a 911 operator, Anthony has this extraordinary capability to get beneath the surface. To listen to what’s said, but more importantly, to explore what’s unsaid.

And I hope you took some notes about how he says to tread lightly when it comes to dealing with what’s unsaid.

Thanks for listening.