Apple Award Winning Podcast

Level Five listening is listening for meaning.

It’s the difference between listening to the speaker and listening for the speaker.

Recreational listening is listening to the speaker – just the words that they’re saying. But when you’re listening for meaning, you help the speaker to make sense of what they’re really thinking.

The meaning goes beyond the present conversation, and into the future. What are the consequences?

In this episode, Oscar and Nell unlock how to listen for meaning for both individuals and for groups. Learn how to listen for the capital letters, and from real-life examples and audience questions.

Join us on the final step of the journey, to becoming a Deep Listener.

Transcript

Podcast Episode 059: The Five Levels of Listening – Listening for the Meaning

Anthony Weeks:

One of the things I learned from her was how to listen for capital letters, and by that I mean she listens for those points of inflexion or points of emphasis where if you could visualise it in your mind, they would be saying them with capital letters and so listening for those capital letters to say, “Ah, that’s it. That’s what they really mean to say.” Or “That’s important to them, I’m going to write that in capital letters because that sounds like it’s a big deal.”

Anthony Weeks:

I think that sometimes when I’m listening, listening, listening, people will set up something by saying, “So what I really mean to say is,” And that’s just a softball. I mean, that’s really easy. It’s like, okay, I got that. They’re ready to say something important but sometimes it’s more subtle, sometimes it’s more… they’ll be saying something and then they’ll sigh and they’ll stop, and they’ll give a moment of silence and then they’ll say what they really want to say, and so when you listen for those cues, and when you listen for those points of direction where somebody is about to say what’s really important to them, then I think you get a little bit more attuned to listening for the capital letters and listening to the meaning that they’re about to provide you.

Oscar Trimboli:

Deep Listening: Impact Beyond Words. I’m Oscar Trimboli and this is the Apple award-winning podcast, Deep Listening, designed to move you from an unconscious and distracted listener to a deep and impactful listener. Did you know you spend 55% of your day listening, yet only 2% of us have had any training in how to listen. Frustration, misunderstanding, wasted time and opportunity along with creating poor relationships are just some of the costs of not listening. Each episode of the series is designed to provide you with practical, actionable and impactful tips to move you through the five levels of listening.

Oscar Trimboli:

I invite you to visit oscartrimboli.com/facebook to learn more about the five levels of listening and how to learn from others who are listening better. Joining me is our co-host Nell Norman-Nott who will ask the questions that you’ve been asking and asking me the questions I haven’t considered to help make you a deep and impactful listener.

Oscar Trimboli:

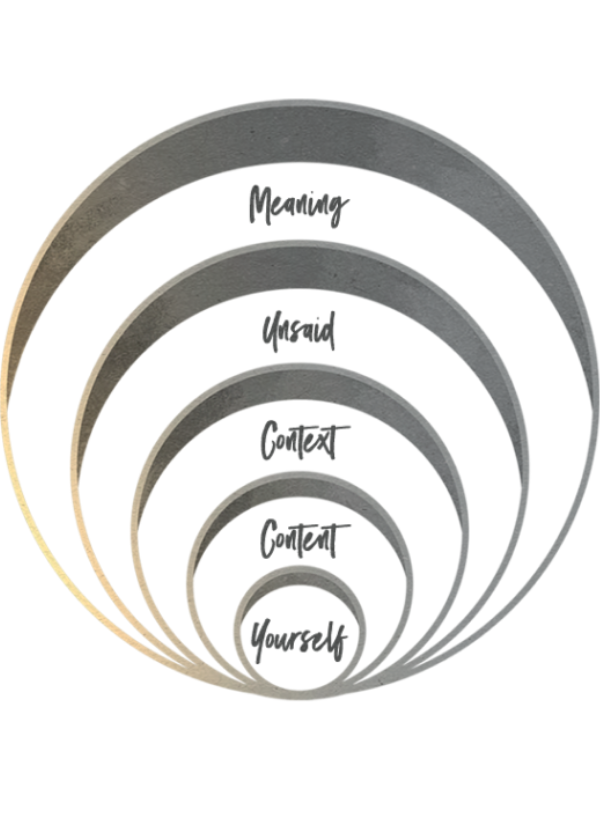

I’m often asked what deep listening is and what I say to most people is you listen in black and white, you listen in two dimensions. Deep listening is technical listening. It’s listening in five colours. In today’s episode of Deep Listening: Impact Beyond Words, we reach the summit, level five deep listening. Listening for meaning. We explore the fifth level. This is listening for the meaning. In our previous episodes, we deconstructed and explored all five levels of listening. Level one, listening to yourself. Level two, listening to the content. Level three, listening for the context. Level four, listening for the unsaid and level five listening for the meaning.

Oscar Trimboli:

When I think about what distinguishes recreational listeners from deep listeners, these are the two words that separate them. They’re two simple words, [Nell 00:04:04]. The two words are, to and for. Recreational listeners are listening to words, sentences, stories, and to make sense of what the speaker’s saying for them. Deep listeners are listening for, they’re listening for what’s beyond the words. They’re listening for what’s beyond the sentences. They’re listening for what’s beyond the stories. They’re listening for the context. They’re listening for the unsaid and they’re listening for meaning, and they’re listening ultimately for the speaker and they’re listening ultimately not to listen to the speaker, they’re helping to listen for the speaker.

Oscar Trimboli:

They’re listening first to help the speaker make sense of what they are saying and what they’re thinking. They are listening first to help the speaker make sense of what they’re saying and to make sense of what they haven’t said so far what else they’re thinking about. The 125-900 rule says the speaker can think at up to 900 words per minute yet they can only speak at 125 words a minute and then there are nearly 800 words stuck in their mind while they’re trying to get them out. A deep listener understands that they are there to help the speaker hear what they’re thinking.

Oscar Trimboli:

Recreational listeners are listening to themselves. They’re listening to make sense of what’s being said for themselves. Deep listeners are listening for the speaker. They’re listening for the speaker to understand what they mean not just what they’ve said. Deep listeners are listening for the others and ultimately at level five we’re listening for meaning. The meaning that matters the most is what is being said means something to the speaker. It’s their own meaning. Level five listening, listening for meaning also explores when they are listening beyond the individual discussion and you start to listen for meaning in groups, in teams, in organisations and in ecosystems.

Oscar Trimboli:

At level five listening, you start to listen well beyond the boundaries of the organisation and the timeframes. You can start to listen for what it means next year or last year or for the next generation or many generations to come. In today’s episode of Deep Listening, we’ll explore how to listen for meaning in individual discussions as well as group discussions. Joining me today is my co-host Nell Norman-Nott who always ask the questions I haven’t thought about and ask the questions that she knows are on your mind.

Oscar Trimboli:

Nell, as we expand on what listening for the meaning is, we’ll do it in two different yet overlapping ways. Listening for meaning for someone else and listening for meaning in the groups. As I open up the Deep Listening playing cards and explore the [inaudible 00:07:14] it outline some wonderful questions that you might like to explore. What can we explore that makes a bigger impact? What perspective beyond our own can we explore together? What’s different in your thinking since we started and if we had 24 hours more to think and discuss this, what other opportunities do you think would emerge, so Nell, have you had a chance to spend some time with the Deep Listening playing cards as much as I have?

Nell Norman-Nott:

Probably not as much as you have Oscar because you wrote them, but they sit on my desk and I’ve used them in different ways. We started working together when I was working at LinkedIn and so I have used them for starter ideas when I’m going into meetings with someone within my team there or at a particular team meeting that we might’ve had. I also now use them really as reminders because this stuff, there’s a lot to understand and I think it’s the repetition and understanding and reading it over many days and a lot of time that it actually is beginning to sink into my mind, so that’s how I use the cards. I think they are beneficial to so many different kinds of scenarios and situations. To take a look at how you can use them, go to oscartrimboli/cards and you can also buy them from that page as well.

Oscar Trimboli:

Hey Nell, a secret you don’t know about, but in the background I’ve been building an online programme for leadership consultants who can learn how to use the cards in other situations and I’ve interviewed a range of leadership consultants and if you want to learn more about how to get access to that site as a leadership consultant, just send me an email at oscartrimboli.com and you can become part of the early prototyping on that online site.

Oscar Trimboli:

Thinking about listening at the level of meaning helps us to make sense of the discussion and informs a wide range of both perspectives and possibilities. Nell, let’s remember that for most of us we need to progress through each level of listening to become proficient rather than to master the level below and for most of us, our goal should be to become proficient at level one and level two as Heidi’s research explains, 86% of people are struggling with avoiding distraction, keeping their attention on the conversation and on the speaker.

Oscar Trimboli:

If you haven’t had a chance to listen to episode 55 where we unpick all of the research, or maybe you’d like to download the research yourself, visit oscartrimboli.com/research and you can download the research and it explains not only what people struggle with, but also how we discover the deep listening, listening villains as well. Now, one of the things people tell me is that listening at level five is transformational. It’s transformational for the individual listening. It’s transformational for the speaker and it’s also transformational as part of the system that we think about and Nell, you had a bit of a transformation in December last year when you went back to the UK for a while.

Nell Norman-Nott:

That’s right. I went back to the UK in December last year because it was my dad’s 80th birthday. My dad is one of those people who’s really hard to buy for. I think we all have one of those in our life. I know who that is in your household, Oscar and your wife [Jenny 00:11:03] would definitely know who that was.

Oscar Trimboli:

Yeah, you mean that’s me.

Nell Norman-Nott:

But seriously, what do you get someone when they turn 80. My dad is fit, healthy, he’s still working as a psychotherapist and a lecturer. He has everything he needs. The idea for his present came around eight months earlier when I was chatting with my sisters and my brother, Lou and Steve. Lou mentioned that she had in her attic in her house in London over 400 letters that were written during World War II between my grandparents, Joyce and Doug Hinshelwood, my father’s parents.

Nell Norman-Nott:

Doug was posted to various points in England and in Europe with the Royal Air Force during the second world war, whilst Joyce remained in the South of England in Surrey and several places in the East of London raising my father and his brother John. To relate this all back to the topic of meaning, those letters had meaning for the family, but they were just a bundle in the attic, so really meant little to anyone else. As siblings we decided to produce a book of the letters for my dad’s birthday. When we initially talked about it, I was like, oh, that doesn’t sound too difficult to do. There’s four of us. We can get through that, it’s quite achievable. We’ve got around six, seven months and we also realised my uncle had already transcribed many of the letters so that they were in a document on the computer already. However, between us we needed to proof them all, we needed to check that they’d been transcribed correctly.

Nell Norman-Nott:

Some of the letters had been damaged over the many, many years that they’d been sat in the attics, so things had been illegible so we had to go back and try and decipher them. Some of the dates didn’t seem quite right through a lot of acronyms and abbreviations. In fact, we created a whole directory at the beginning of the book to explain what some of these acronyms meant and there were also words and terms that I’d had never heard, something called [ketar 00:13:20], Oscar, do you know what ketar is?

Oscar Trimboli:

Yeah. It’s a tightness on the chest.

Nell Norman-Nott:

Tightness on the chest.

Oscar Trimboli:

Phlegm.

Nell Norman-Nott:

Phleg… That is exactly what it is. There’s a lot of talk in the letters about phlegm, which surprised me because these were kind of mundane, everything’s to do with raising the children, but it was happening at a really unique time. It was during the second world war, the Nazis were dropping bombs on London to the point where London nearly surrendered and in fact, my grandparent’s house where my father was living was bombed. They weren’t in it at the time, otherwise I wouldn’t be here today. They were away, but they came back from a weekend away or a holiday and the house didn’t exist anymore, so they went to live… my grandmother, my father and his brother went to live in a relative’s house and so they were in this little three bed semi in East London and the letters are about my grandmother and her raising the two boys.

Nell Norman-Nott:

It’s everyday life. It’s… they get sick. They had chicken pox, there was no vaccines in those days, whooping cough, learning to walk, first days of school, day to day things. My dad, maybe not being that bright was in one of the letters, which was quite interesting and we all had a good laugh about that. So, through these letters we gained more meaning about our relationship to one another. I live in Sydney, I’ve been here now for 10 years and my siblings are all in the different parts of the UK and they maybe don’t see each other as much as we all used to, so we brought us close together. There was that transformation depth around our relationship.

Nell Norman-Nott:

The project was also… brought meaning to the letters because we produced this book. Now my sister Emily is an author and so she was able to leverage a lot of her connections and to publish the book so it is published and the British Library have taken it now into their collections, so it not only has meaning for our family, it contains all the letters. It contains all photographs from the time we gathered photos of things like Anderson shelters, which is where people went during the bombing and during the raids in London and those are interweaved with the text and with the copy so that now these letters can also have meaning as part of social history at a time which was very traumatic and very impactful for everyone living there but it really was a normal family life.

Oscar Trimboli:

I’m wondering what it meant to your dad. How did he react when he got the book?

Nell Norman-Nott:

He’s not an emotional person. He’s a very calm person and he was visibly emotional when he saw the book. He couldn’t quite believe what it was when we gave it to him.

Oscar Trimboli:

And how did the rest of your family react watching your dad like this?

NellNorman-Nott:

Oh, I mean they were all absolutely fascinated. They immediately said, “Can we have a copy?” And we printed 50 copies so that we could give them to my uncle and to their children and their grandchildren, because as soon as everyone saw it, they wanted a copy because it’s got relevance to so many people as well.

Oscar Trimboli:

Nell, a really good example when we operate at the level of meaning is that not only meant something to your dad, it meant something to you, it meant something to your siblings and to your dad’s brother and to many, many generations beyond that as well, and that’s the point when you’re listening at the level of meaning, it has a depth that goes well beyond just the conversation and the interaction that’s happening in that moment. As you said, it’s a legacy. It’s a legacy not only for your family, but it’s a legacy in the British Library as well, so that will have relevance for many years to come. Well done on a great project, I hope you feel proud because I’m sure your dad does even if he didn’t say it.

NellNorman-Nott:

I feel proud. It was a really fun project to be part of and I almost felt a little bit of mourning afterwards to not have that as a connection point but I don’t think we can have a [inaudible 00:18:01] that is a present in the future.

Oscar Trimboli:

Nell idea’s birthday parties remind me why it’s so important to celebrate life and this reminder came to me in episode 12 where I interviewed Bronwyn Brooks, who’s a funeral director who catches people sometimes before they’ve left this planet and sometimes discussing their relatives there. Well, let’s listen to a wonderful story about how meaning can show up differently when you’re not listening carefully.

Bronwyn Brooks:

I often use the analogy, back to the funeral director world, how many people coming to me and would say “I just want to put mom in a cardboard box.” And that was really, really common. Learning how to have that conversation with families, what do they mean by putting mom in a cardboard box? Often that means they don’t want to spend a lot of money on a coffin. The company I work for, they had a range of cardboard boxes, which actually cost more than the hardwood coffins.

Bronwyn Brooks:

Finding out, was it an environmental reason that they wanted to put their mother in a cardboard box? Just having that conversation, I thought that was another example of listening and working out, what are people’s reasons behind what they’re saying, and is what they’re saying what you think they mean?

Oscar Trimboli:

What I like about the way Bronwyn listened during the story was, she suspended judgement and she helped them find their meaning. Listening for meaning at level five can be as simple as asking the question, “What does this mean for you.” Subtly and dramatically different you can also ask, “What do you mean?” What does this mean for you, helps the speaker explore those extra 750 to 800 words that they have swirling around in their mind. Are there any swelling around in your mind at the moment, Nell?

Nell Norman-Nott:

I really enjoyed listening to Alan’s Stokes in episode two where he talks about listening for someone else and not for himself.

Oscar Trimboli:

Yeah. I think Alan draws a clear difference in listening from your perspective to listening for their perspective.

Alan Stokes:

I think it’s a fairly clear dichotomy. When there are two people in a conversation and one person’s going through a struggle, sympathy is about the person who is hearing about the struggle. It’s all about me, me, me. I am feeling bad for you. That’s a selfish thing. It’s well-meaning, sometimes it can be helpful, but basically it’s about, I need to feel sorry for you because of what you’re telling me. If you think about that deeply, that doesn’t help the other person. What helps the other person is empathy, and that is being there with them. It’s about them, so our aim at Lifeline is to offer empathy, which means, it’s about them.

Alan Stokes:

It’s not sympathy about me and what I think and what I feel about, oh how bad it is for someone else to go through a break up, or a mental health issue, or whatever. It’s about them and what we can do to support them to get through their crisis and that’s where refection’s crucial, because reflection by definition is you giving back to someone else what they’ve just told you either in content or in broader meaning or in feeling. In the one action of reflecting you are acknowledging that you’ve heard. You’ve really heard.

Oscar Trimboli:

Can you feel, can you notice Alan’s primary orientation is focused out. It’s focused on the speaker because it’s the result of progressing through the other full levels of listening that Alan can help the speaker start to explore their own meaning. Alan has a ritual before he gets on to a telephone to prepare himself at level one to listen to himself, and then goes through a very deliberate process of checking in to make sure that the minute he picks up that call, he’ll be listening for what they mean. I think Alan makes this point really well.

Oscar Trimboli:

It’s about being there with them rather than feeling sorry for them. It’s this orientation that Alan holds that helps him make an impact beyond words. When Alan is listening for their meaning, rather than trying to make sense of what they’re saying or trying to make meaning from the discussion only for himself. Yet Nell, whether you’re dealing with life or death issues as a lifeline counsellor on the telephone, sometimes honestly, meaning can come from the kitchen sink. It can come from something as simple as dirty dishes.

Oscar Trimboli:

I don’t know about you Nell, but sometimes if I come home after a day and there’s dirty dishes in the sink, I make up a lot of stories about who those plates belong to and why they should have cleaned up and in doing that you can notice I’m in judgement , I’m thinking about myself and I’m not thinking about them.

Nell Norman-Nott:

I think that’s a very common feeling, Oscar. The thought that so many people must have when they walk home, whether you’re trying to maybe park your car and you realise there’s only one parking spot, but the really ignorant, selfish person next to that spot, parked their ties over the line so you can’t get in there. What were they thinking? But you know what, it might not have been them. It might just be that the person before them on the other side hadn’t parked quite in the space and it’s not really their fault, but yeah, you’re right. I feel like we jump to those judgements so easily.

Oscar Trimboli:

I get worked up about the dirty dishes not only at home, but I’ll walk into a lot of workplaces. We see lots of dirty dishes in the community kitchens and lots of signs about the importance that everybody should be putting away and cleaning up after themselves and I think you can judge a lot about a workplace by it’s kitchen. Sometimes kitchens at home, they might be teenage kids or warring parents, sometimes we make dirty dishes mean so much more than they really do. In episode seven, Ken Cloke recounts a powerful story about the meaning a couple made from dirty dishes during this conversation.

Ken Cloak:

A couple comes to see me and we spend a couple of hours together and it’s very useful, and they walk away and they feel good about the conversation we just had, so they come back a week later and I say to them, “How has it been this last week?” And he says, “Great.” And she says, “Awful.” Well, awful trumps great, so you can’t say what was great about it, you have to go instead and say, “Okay, what was awful?” And she says, “Well, just this morning as we’re leaving the house, he left his dirty dish in the sink.” And he rolls his eyes and go… has a huge sigh and says, “I can’t believe you’re bringing that up.” And she says, “Well, that’s just like you to pay no attention to what I want and to the things that I object to.” And now they’re off and running. So, the argument goes on and on.

Ken Cloak:

Here’s the basic situation. They’re getting in to this huge argument and the emotions are getting very hot, and the thing that they’re arguing about is a dirty dish in the sink, and those two things don’t match. If they don’t match, in other words, if you can’t make an equal sign between them, it means there’s something else other than just the dirty dish in the sink, and the other thing that there is is the meaning of the dirty dish in the sink. So, I say to her after they’ve argued a little bit, “What did it mean to you that he left his dirty dish in the sink?” And she said, “It means he doesn’t respect me.” Okay, now that’s significantly more important.

Ken Cloak:

You can understand why somebody would get upset not so much about a dish, but about respect, but this even doesn’t go quite deep enough, because I can tell from their argument that this has touched a deep place inside of her. She’s really upset about this and he doesn’t get it, and so, I say to her, “What does it mean to you that he doesn’t respect you.” And she says, “It means he doesn’t love me.” Okay, now we’ve got it. The dirty dish in the sink doesn’t just mean the dirty dish, it means he doesn’t respect her and because he doesn’t respect her, it means he must not love her, and now his mouth drops open because he can’t believe that we’ve gone from this dirty dish to the fact that he doesn’t love her, and so he’s kind of stunned and so I turn to him and I say, “Is that, right?

Oscar Trimboli:

Nell, I love the simplicity, the elegance and the surgical precision of Ken’s question when he said, “What did it mean to you?” And then he carefully and skillfully just went a little bit deeper.

Nell Norman-Nott:

I’m curious how much we must bring this kind of association between unrelated actions and feelings in the workplace as well as at home and how attention such as those experienced between the couple could also play out in that corporate environment, although not exactly the same. I could see how someone feeling disrespected because of something that someone else did at work, taking that tension into the next meeting that they went into.

Oscar Trimboli:

Now, listening for meaning in a group setting is potent and powerful. Helping a room come to a collective meaning is extraordinary. Sarah Manley who talks about this in episode three is a graphical facilitator and she does a brilliant job of helping the room to come to collective meaning.

Sarah Manley:

When you’re really in the zone as a graphic facilitator one thing that you can do is make connections within the conversation that are not obvious to the speakers, and this is possible because of your experience, also your level of listening and also the fact that you are an outsider to the conversation. I feel like the times when we’ve used scribing to its greatest success is when… it’s not even obvious until we’re finished with the conversation and everybody steps back from the board and looks at it and says, “Oh man, that’s what we said. That’s how it is. That’s what we said”. And so being able to present a model of this organisational issue that they can then use to communicate to other people.

Sarah Manley:

I mean, I really feel like we’ve done a good day’s work when we’re able to do that. When the client’s able to look at the drawing that we produced and understand their issue a lot better because it’s been filtered and connected and interpreted by another listener.

Oscar Trimboli:

Sarah and all the graphical facilitators do a great job of helping a team, a group or in Sarah’s case even ballrooms and convention centres full of people to make sense of what’s being discussed. Another technique to help bring out the new and the possible, the more effective and different meanings as work based practises is known as the [Philosopher’s Walk 00:30:49], where groups of two or three people walk around the meeting room and look at the graphical artefacts they’ve created on a wall or there could be printouts that have been stuck to the wall as well.

Oscar Trimboli:

Walking around the group discusses with each other what it meant for them individually and then posing the question, “What do we think it means for the group, the team or the organisation. In reflecting back to others what it means, the result is another layer of meaning is constructed for the room as the room debriefs itself, understanding what it means for them. Nell, it reminds me of a story. I was doing a facilitation. It was out near the Sydney Cricket Ground. It was old bank building that had been renovated. The building is now called The Vault and it has beautiful 1890s architecture. It’s quite cold in there because the walls are so thick and the reason the walls are so thick was because it was a bank vault that stored bullion as well as cash and the biggest concern as I looked into the history of this venue was that people would come along and literally knock down the walls of the bank and take the money out during the nighttime because the vault stands alone.

Oscar Trimboli:

Anyway, I digress. When I facilitate a workshop with teams, one of the things I’m very deliberate about is asking the teams to reflect on the past as well as the future. Too many planning workshops and they’ll spend way too much time thinking, talking and actioning the future and not enough time acknowledging the past. What brought us to where we are today, and when I initially proposed this to leaders that I’m facilitating on behalf of, I sense a bit of tension, they don’t want to go to the past. They just want to look to the future, but there’s a reason we have funerals, Nell. We have funerals to celebrate the life of that person who’s passed for the living, but we also want to acknowledge what they’ve achieved.

Oscar Trimboli:

Too much work in corporate spends all its time focused on what’s going to happen. I’s awesome, wonderful, amazing in the future. Without acknowledging the past which built the foundation that got us here, not only the past and the foundation that got us here but what from the past are we going to take forward and what from the past do we choose to leave behind? I often do this exercise and I ask groups to have a conversation with each other individually and then collectively about what from the past they want to leave behind and what from the past they want to bring forward and I do it in that order for a reason.

Oscar Trimboli:

Most of the time is spent in a conversation about what do we want to leave behind. That’s where the tension is. That’s where people make meaning of certain things and in this workshop, what they were making meaning from is a practise, a ritual, a routine called the daily stand-up, a 15 minute meeting where everybody working on a project comes together and discuss what happened yesterday, what they’re working on today and what they might need help on from others, and the exercise was finished and what the group had come to a decision on was nothing. They hadn’t decided, they were stuck about whether they should progress and bring the stand-up forward or leave it behind, so I pose the question to the group. Noticing where your team is now stuck about the stand-up, what does that tell you about the stand-up?

Oscar Trimboli:

I created enough tension and courage for someone in the group who was an introvert to speak up and they simply said, “Stand-ups are a complete waste of time.” We go through this ritual, we make ourselves feel better, but we never question how productive we could make the stand-up, and I explained three things they would do to make the stand-up more productive and for them the stand-up meant 15 minutes of their life that they’d never give back, so I simply posed the question, “What else?” And other people started to jump in, some people saying the stand-ups are really worthwhile to them.

Oscar Trimboli:

It meant a lot to them, and as a result what the leader noticed and came to me at the break and said, “We’re going to take the stand-ups forward but in a completely different way.” And it was the skill the leader displayed in that moment where he asked the person who said, stand-ups are a waste of time to lead the stand-ups going forward. After the break we had a 15 minute stand-up about how to run the stand-up and it was really interesting because the person who’d spoken up initially said this should be the way stand-ups are run going forward rather than simply going through rituals, going through routines and going through the motions, and I’d pose the question to you if you’re listening as a leader right now and you’re part of the stand-up or you’re a listener who is in a stand-up and don’t want to speak up.

Oscar Trimboli:

Take one stand-up a month aside and just simply ask the question, “How could we improve the stand-up rather than going through the motions, the rituals and the routines of stand-up and you’ll notice a transformational impact. [inaudible 00:36:41] the clock forward six months after that workshop, Nell. I get a call from the guy who said we should leave the stand-ups behind and he said, “Wow, thank you. The way you got our group to talk about the stand-ups is fantastic… they’re in software industry. We’re sorting up bugs faster, we’re integrating client feedback faster, but more importantly we’re having honest conversations about what everything means to us, whereas in the past we just went through the rituals and the motions.” My point is really simple, Nell. If you don’t know what meaning people are making out of these rituals, they can become quite pointless.

Nell Norman-Nott:

Oscar, those stories about your experience running workshops is so fascinating to listen to. What other examples have you got?

Oscar Trimboli:

The one that comes to mind is probably about two and half years ago. It was a people manager meeting where I was invited in to speak about deep listening, so visualise a room with chairs in theatre style and there was about 80 people, but it was a narrow room so there was only six wide and whatever that works out about 20 deep, probably more 25 deep, so it was quite a narrow long room. It wasn’t ideal for presenting in and I was speaking on the topic of deep listening. Nell, have you ever walked into a room where you could cut the tension with a knife?

Nell Norman-Nott:

I’ve definitely been in rooms like that.

Oscar Trimboli:

And as I spoke at the 10 minute mark and at the 20 minute mark, I could feel the tension getting higher in the group and some people call it this Spider-Man tingly feeling, other people just go with your gut feel and for me it was like making sure my attention was on the room, not on me and what I was presenting and this tension was there. I could taste it, I could smell it. It was kind of like mildew that was dripping through the building and it’s a manufacturing organisation and there’s about 500 people in this organisation and about 80 people managers and at the 30 minute mark of this meeting, I just stopped. I turned to my host who was sitting in the front row and just said, “Do you trust me?” And he kind of gave me this look of confusion.

Oscar Trimboli:

I said, “Look, I’m going to ask the room a question that’s got nothing to do with the topic.” Because I sense the room’s in a different place and he goes, “Do I have a choice?” I said, “Yeah, you have a choice. I can continue on.” He says, “Well, ask the question anyway.” He didn’t say it in a dismissive way, but he was frustrated for sure but we’d built up enough rapport that he trusted me, so I said to the room, “Turn to the person next to you. If the last seven days was a movie, what movie would it be here in this organisation?” And the room exploded into noise and people turning and talking to each other and lots of laughter and the energy dynamic changed quite dramatically and the leader came up to me and asked me to switch my mic off and said, “What the hell is this about?” And I said, “Don’t you feel what’s going on in this room? Don’t you sense the tension?”

Oscar Trimboli:

He goes, “I’ve no idea what you’re referring to.” And I said, “Okay so I’m going to bring the group back and they’re going to tell us what movie they’re at. I just need you to be patient. I need you to listen. I need you to kind of just think about the patterns and what people were saying.” It was hard to bring the room back because they were off. They were telling each other what movies and all of that and it wasn’t the movies I liked. What they said was… the movies that came back was Die Hard with a Vengeance, the Titanic, The Towering Inferno. Name a disaster movie, Nell and they were telling me about it and every time the movie title was mentioned, the audience would break into laughter.

Oscar Trimboli:

There was one person who wasn’t laughing, that was the leader in the room, and I paused, and I used the silence and the leader did something extraordinary at that point. He asked me for my mic, he took the mic off me. He asked me to take a seat and it was in that moment that I went, “Oh, well, not getting paid for this.”

Nell Norman-Nott:

You don’t do this for money Oscar, you do it for love.

Oscar Trimboli:

And he stood up in front of the group and said, “I’m sorry. I don’t ever want to work in any organisation where people feel like coming to work is a disaster. I need your help. I need your help to solve this. What I’ve done obviously hasn’t worked. Can we do this together?” Now, what we did in the last 20 minutes of that workshop was to throw away the deep listening the agenda and I posed the question about who are we listening to as this community? And the group said some of the most obvious people on the front lines of this manufacturing site were the people that weren’t listening. The backstory, listening for the context. Level three, if we go back there now, what was happening was that there were some impurities in the production line which meant quality assurance wasn’t able to verify that the sterile stock was able to be released to the general public and there were millions of dollars worth of stock being held up in this environment.

Oscar Trimboli:

What they’d been working on for three months is they continuously thought they’d solve the problem only for it to reappear week or two later and the fix that they’d put in wasn’t the fix, it was just that the pipelines were clean for a while. In the asking the production staff how to help them with solving the problem, they solved the problem in three days, not three months. How many situations are you not listening to your frontline workers, in whether that’s bank tellers or customer contacts and the people, but the point of this isn’t about stock or quality or anything like that.

Oscar Trimboli:

The point is, if you ask people to explain a really complex topic through a movie or a book, it gives them permission to tell the truth. They would never have told this leader that it was a disaster coming to work everyday, yet the movies allowed them to speak the truth and that’s where you can have an impact beyond words, and in this case many millions of dollars by just listening to what the room’s doing because the consciousness we need to have is to have our attention on what was the state of the room, not how nervous I was as speaker.

Oscar Trimboli:

By the way, I was very nervous as a speaker, but I always am. As the world champion deep listener it’s like speaking is my evil villain. That’s one of the stories for me that brings meaning to life. I think that simple act of you channelling the audience and asking me that question about my consulting work, that was really powerful because you’re pulling out these stories that have come from my work and I’d encourage others to ask me those kinds of questions. We love hearing from people who are listening to the podcast. How would you suggest they connect with us?

Nell Norman-Nott:

You make a really good point, Oscar. I could see how… I mean I get insight into you day to day and I hear how many fascinating stories you’ve got to tell, which is why I wanted to draw that one out of you when I asked that question. It’s really simple to contact us. Go to the website, www.oscartrimboli.com, you’ll see on the right hand side, there’s a button you can click to send us a voice message. You can also send us an email to podcast@oscartrimboli.com with your question in it there, but for now we’ve got some questions that have been asked and we’re going to go through and play those now.

Cliff:

Hi Oscar. It’s Cliff here from Sydney. I wonder when you spend your day listening to people, do you go home with an empty battery for listening? Keen to get your thoughts.

Oscar Trimboli:

You know, Cliff, when you spend 93% of each day, each week listening, you need some really practical ways to recharge those listening batteries. In the early days did I go home with listening batteries completely depleted and needing a recharge? You bet you, so the strategies are put in a place were pretty simple. It’s probably about an hour commute from where I work to where I get home, so one of the things I’m big on is to kind of change the frequency when it comes to my listening. Rather than listening to conversations, I listen to music on the way home.

Oscar Trimboli:

I find that completely changes the frequency of how I listen and when that’s not working for me. What I do is listen to absolutely nothing. There is an app called [Coffitivity 00:46:30]. Coffitivity is an app that just plays the sounds of things in coffee shops, the sounds of a coffee machine, of cups clinking or I might just simply play the Headspace application on my phone which is a meditation app or Insight Timer. Either one of those help me recharge my battery, but if you do spend a lot of your day listening, you absolutely need to recharge those batteries. Hope that helps. Cliff.

Jade:

Hi Oscar, Jade here from Melbourne. In a group situation we often find varying abilities to listen. How could I show others through my behaviour and my ability to listen to make sure that others in the room can make the right space to sit in the silence and to really show everyone that we can listen deeply?

Oscar Trimboli:

Thanks for that question, Jade. A lot of it is about what we role model and what we show. It’s about getting set at level one, listening to yourself. Are you as the leader ready in the room for the conversation? Have you cleared everything out of your head before you start? I’ll get distractions out of the way. Have you told the room that your phone is switched off and in a bag or in the corner? Not on the table. Are their laptops present? Is yours present? Can you take your laptop out of the room or your iPad? Is, everybody got water? And are you noticing your breathing? Three simple tips for you to help role model listening to the room.

Oscar Trimboli:

Sometimes we get confused that we say silence equals deeper listening, but I think we all need to start right back at the beginning as leaders in the room and just role model what it means to be a great listener, and that’s to be ready to listen. I think if we can start with those three things, we’d make a huge difference in the world, Jade.

Melanie:

Hi, this is Melanie in Michigan and I’ve noticed that my communication challenges are directly tied to technology and specifically my cell phone. I have noticed that if I’m on my phone doing something for fun or even for work, that when people talk to me or interrupt me, that I still tend to look at my phone and I’m aware that that’s poor communication. I don’t appreciate it when that happens to me when I’m trying to talk to somebody and they’re looking at their phone, so my challenge and my question would be, really how can we balance using technology, being productive but still being present and available for communication with our coworkers and also with the people in our lives that we love, so thank you very much.

Oscar Trimboli:

Thanks Melanie, and building on Jade’s point, let’s think about in the moment if it matters. If this conversation truly matters, do we need our phone? And you talked about productivity, I agree. We need to be productive but for the time we’re listening, why not put the phone away and signal to the other person that they’re so important that we’re doing that. If we need the phone to take a note or something else, then let’s bring it back and I’m sure the person you speak to would wait for it. If you signal to them and say, “Look, this conversation is really important to me.” What I’m going to do is I’m going to put my phone over there on the bench or in my bag or this conversation’s really important to me. I’m going to put my phone in flight mode. It’s going to be on the table but it won’t buzz and it won’t ring.

Oscar Trimboli:

When I have something important to say, which I sense is what you meant by productivity, Melanie, pause at that point and ask them, “Is it okay if I can take a note on my phone. Make the note on your phone or on the app, but once you do switch it back into flight mode. If you need to take it out of flight mode that is, and then put it back again. You’ll start to realise that you’ll hear things differently but more important, you’ll listen in a completely different way and it’ll transform your relationship with them and the productivity that comes as a result of hearing things that aren’t said will be amazing. Practise that Melanie and let me know how you go.

Marlise:

Hi. Oh scar. This is Marlise from Amsterdam. I feel that deep listening is super effective in most settings. Be it a business meeting or a training environment. However, I was just wondering are there any situations in which you wouldn’t recommend deep listening in which deep listening doesn’t make sense?

Oscar Trimboli:

Marlise, this is a great question and one I actually get quite frequently. When is deep listening unproductive? When is deep listening ineffective? When does deep listening get in the way of progress? I think we need to notice a couple of things. Our patterns recurring in the dialogue that’s taking place when we’re having discussions are the same themes coming up and not getting resolved. Whether that’s within that conversation or over an extended period of time. Imagine a work in progress meeting on a project where every month the same issues get raised but they’re not getting resolved.

Oscar Trimboli:

I think in those moments, deep listening doesn’t become effective. I think deep listening is effective only when we have a bias towards action. What do I mean by that? I mean, the difference between hearing and listening is the commitment on both parties, the speaker and the listener to take action. The difference between hearing and listening is action. When is deep listening unproductive? When there isn’t a commitment to action. I hope that helps.

Andrew:

Hi Oscar. It’s Andrew from Orange County, California and after a bit of thinking, I’ve realised that I struggle with allowing silence, especially when I’m in client meetings. When I feel like I need to be in the driver’s seat the whole time. Do you have any suggestions on how to make a bigger impact with my listening when I’m running these meetings? Thanks.

Oscar Trimboli:

Hi Andrew. Great question. The answer is in your own question. When you said, “I need to be in the driver’s seat.” Do you really? Are you attending those meetings for you or are you attending those meetings for your clients? My sense is if you spent a little bit more time asking the client about the agenda the meeting would be easier, would be smoother, would be more conversational, would make more progress, and your impact would be more significant, so take your mindset into your next meeting to go, “How can I ask a question to understand a bit more about their situation and how can I put them in the driver’s seat?” Sometimes it’s fun being a passenger. You see the world from a completely different perspective whilst helping them navigate their way into their future. Let me know how that goes Andrew.

Nell Norman-Nott:

Oscar, I love hearing those answers to the listeners questions because they’re real world situations which must be relevant for so many people and the responses you’ve given are so practical and helpful. I’ll definitely be using those in the future. I’m curious because I feel like we get so many questions. We need a format to be able to add these to the podcast in the future. How about we have a regular segment in each podcast where we talk about the listeners questions and you address them based on your experience?

Oscar Trimboli:

Yeah, I think let’s pop it in at the end maybe, or maybe at the beginning. Why don’t we let the listeners decide where the question should go and let us know podcast@oscartrimboli.com. Send us your questions, send us whether you think we should do a standalone Q&A session for the podcast or integrated into the episode. Remind me of a question I got only a couple of weeks ago, Nell, when I was doing some research for the listening managers masterclass online series that I’m developing. When you’re the listening guy, you have to prototype and listen to your audience and one of the questions that I pose at the end of the 30 minutes of this review of the curriculum I’m putting together for the online course.

Oscar Trimboli:

By the way, if you want to become part of the prototyping for the listening manager’s masterclass, just again send me an email with the heading, listening master class in the subject line. That’s all you need to do at podcast@oscartrimboli.com with the heading, listening managers master class. I always ask this question at the end of the 30 minute review, so this happens at about the 20 minute mark. I said, “What questions should have asked that I haven’t?” And the person who was doing the review with me said, “That’s a good question. I’m just going to use silence, Oscar so just bear with me for a moment.

Oscar Trimboli:

I think he was on his best behaviour and he was internal programme management expert in a government department, originally from India and he was very thoughtful and he said, “Why don’t you do a live Q&A session? I’d attend a live Q&A session, Oscar.” I was freaked out to be honest, Nell because me being live and me having the spotlight on me, not something I enjoy, but if you’re on a quest to create 100 million deep listeners in the world, you better get the hell over yourself and answer the questions, so he challenged me. He said, “Why don’t you do a live Q&A, maybe one morning on the second week of the month, then one evening on the third week of the month and have people either send questions in advance or just ask questions along the way, so I posed the question into the Deep Listening Facebook group and was again encouraged by the group to do that.

Oscar Trimboli:

If you’d like to participate in the live Q&A, go and check out oscartrimboli.com/facebook and you can check out the Deep Listening group and you can learn not only from me and from Nell, but you can learn from others who are on a quest to create deeper listeners in the world.

Oscar Trimboli:

Nell, as we bring the five levels of listening to a close, look forward soon to us unpacking the Four Villains of Listening but more importantly starting to come back to that interview format that you all say you enjoy, whether we’re going to listen to world champion snipers who talk about focus, when we’re going to talk about experts in lie detection and how to look at nonverbal signals, when we’re going to listen to world memory champions.

Oscar Trimboli:

There’s lots to look forward to in the episodes coming up in the Deep Listening podcast series, but before we do, let’s close out and let’s talk about listening for meaning and summarise what’s important as we listen for meaning. Level five, the highest level of listening. Thanks for coming on this journey to the summit of the listening Mount Everest to level five and listening for meaning. When we think about listening at level five, the huge difference is moving from listening to them to listening for them, helping them listen for their meaning through the use of analogies, metaphors, or movies or books or any other ways to get people thinking about their meaning a little bit differently. When you master listening for meaning, you will have an impact beyond words. Thanks for listening.