Apple Award Winning Podcast

Transcript

Oscar Trimboli (00:23)

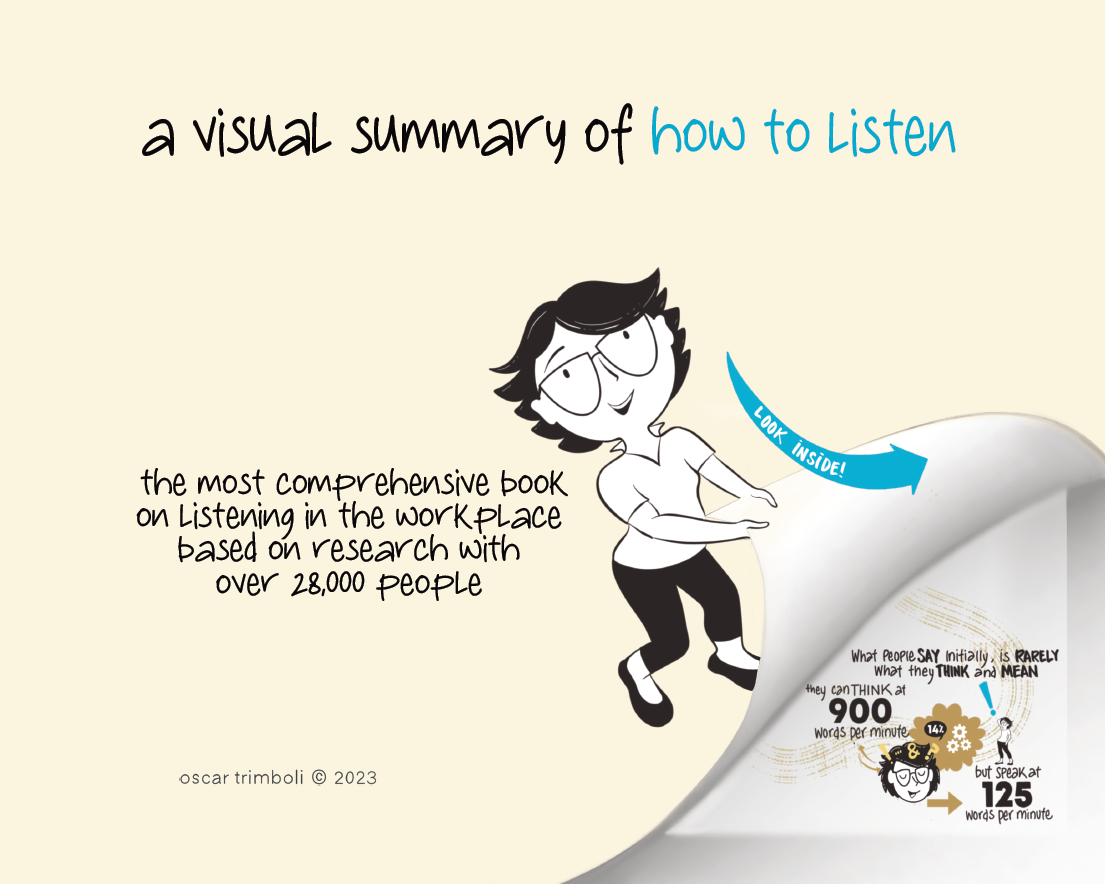

To celebrate the first anniversary of How to Listen: Discover the Hidden Key to Better Communication, the most comprehensive and awarded book about listening in the workplace, we have created a visual summary of the book. Each of the eight chapters are distilled into an illustration from each of the key concepts within that chapter.

The title of chapter five is Explore the Backstory. Great listeners influence how speakers tell their story. In chapter five, we move from New York, to Warsaw in Poland, to England, and then back to New York. Then we travel through the history of the Amazon River. Then we go to Flushing Meadows in the United States to the US Tennis Championship. Finally, to Kenya, and there we discover the impact on the water supply of an ancient battleground.

By the way, if you want to know the origin of[water drop sound], it emerged during the research into over 1,000 tributaries of the mighty Amazon River. Just like over 1,000 members of the Deep Listening Ambassador Community are creating over 100 million deep listeners in the workplace.

Let’s explore three backstories that converge to form this visual summary. The first is from a Deep Listening Ambassador Community of Practice meeting in 2012. The next is from a client workshop in 2021. The final backstory is the reader feedback about the visuals in the book, How to Listen.

Let’s start with the first backstory. It’s Tuesday, September 15th, 2020. And as part of the Ambassador Community of Practice meeting, we’re having a Zoom discussion. And the theme was listening for similarities and difference.

Chapter four is titled Hear, See, and Sense. Listen with all of your body, rather than only with your ears. On pages 116 and 117, there are two diagrams, illustrations, infographics, notes, or real-time scribing from two of the community members, Rebecca Jackson and Heather Willems. What’s fascinating about the infographics, that are the notes taken by each of them listening at the identical time on two different time zones and in two different continents, Rebecca and Heather scribe with some similarities, some overlap, and probably more significant differences.

If we look at Rebecca Jackson’s notes first, she uses a range of icons and verbatim notations. The key theme of the discussion, similarities and differences, is represented by Rebecca as apples and pears. There’s a high ratio of words to images, and a really limited use of empty space or negative space. There’s a deliberate use of sequence. And a linear representation of the development of the ideas as they were discussed.

Heather’s notes use a range of visual imagery also, yet there’s much more empty space on the page. And the ideas carry a different weight, based on the prominence of each idea as it sets in Heather’s page.

When Heather thinks of listening to herself, she uses a mirror. Whereas, Rebecca Jackson draws an image of herself. Heather creates two columns with three bullet points that are blank, representing similarities and differences. Whereas, Rebecca Jackson uses the fruit imagery of apples and pears.

It’s important to understand that you don’t need to be scribe to make sense of what happens in a conversation. It can be as simple as three words that you take a note of. It could be a circle, it could be a triangle, it could have arrows. All that matters is that the diagram you create makes sense for you as a prompt for your memory. Usually, more often, in that moment, to help with recall during the meeting, than necessarily being an artifact afterwards.

Based on the book’s readers’ emails, there are ways that the illustrations created completely different perspectives for different kinds of readers. The feedback I got was very different on Rebecca Jackson’s diagram, compared to Heather’s. It doesn’t make either correct or incorrect. It’s just meaning the ideas are expressed differently. As the feedback started to come in from people who read the book, it got me thinking. I was scratching my head and thinking, “Hmm, is there a way I can create a more useful perspective, a different perspective, by creating a useful visual artifact for people to read alongside the book?” It invited me to think differently about how people absorb abstract ideas, whether that’s written, or diagrams, or using frameworks. It gave me a nudge to think about the visual summary of the book.

(06:00) The second part of this backstory starts on Thursday, March 18th, 2021. Here, I meet Rebecca Lazenby during a corporate professional development conference. Here, Rebecca, or Bec as she likes to be known, was the scribe for the event. And this is the illustration she created of the session that I did about listening. Based on Bec’s understanding of listening, and her reading the book, I invited her to create the illustrations in the visual summary of the book.

Finally, the last part of the book is the backstory. It’s you, it’s the listeners, it’s the readers. It’s the people who are engaging during workshops and providing feedback. And what I notice consistently is that visual images help people engage with these abstract ideas around listening in a much more practical and pragmatic way. Two people could look at the identical visual expression of an idea and take something completely differently from it, whether that’s a mouse, or an elephant, or a conductor. The great thing about visuals is it helps people to internalize the idea where they’re at, rather than where I was at in presenting the information.

What you’re about to see, and hear, next is a discussion between me and the illustrator, Rebecca Lazenby, about the process of bringing the visual summary of how to listen to life. And the role of listening as we work together before, during, and after the visual summary was delivered. Bec and I started by discussing preparation. This project was quite different for Bec. Bec is used scribing at live events, where she creates images that help everyone who’s present makes sense of what they’re saying, and what others are saying. To help people notice what’s being said, what they’ve heard, and how they make sense of it.

The brief about bringing the book to life via this illustration, this visual summary, was the first time Bec worked this way. Although used to scribing in a live environment, this brief, it’s a little bit different. It was mostly conducted over Zoom. And Bec listened to the audiobook, which had a range of character voices in there, as well as a range of sound effects to bring the ideas to life. Very different from reading the printed paperback book, which she did a couple of times as well. What that meant was there was no shortage of information, but the opposite is true too. Because it wasn’t in a real time group setting, it was difficult for Bec to get feedback in the moment while she’s creating these illustrations.

We took the time to create a debrief call about the process, and what you hear and see next is the conversation. To help you understand the backstory about the visual summary of the book, we booked some time to have a chat about reflecting on before the brief, during the exercise of creating the visual summary, and then finally the debrief, what you’re about to hear now. During this, we agreed what worked well, what could be improved. And if we did this next time, what will we do differently?

09:47

Let’s start with before Bec, how did you prepare for the call with me to brief you on putting together an illustration for how to listen for each chapter, which is a significant undertaking? And bear in mind, this brief was done over Zoom.

10:07 Rebecca Lazenby

We spoke, and it was quite a brief conversation to start with, and I really felt like I needed to go off and read the book thoroughly. I’d dipped into it and out of it, but I wanted to sit down and really digest it. I did do that, and then we came back and had a longer brief.

And, for me, it’s always important to get the words first in my illustrations. That comes from working live and needing to keep up with what’s going on in the room, and not getting stuck in what I’m drawing, rather than listening to what’s being said. I really wanted to cement with you what text you wanted me to illustrate. And it was very important to me that the illustrations would support the text and not career off on their own and become their own thing.

10:56 Oscar Trimboli

Bec, our brief took place in multiple parts, a short conversation and then a significantly longer conversation, all via video. Before we got together, how did you prepare for the conversation?

11:13 Rebecca Lazenby

Every time I work, I tend to do a lot of tuning. Usually, I’ll get my space ready. If I can’t be in a quiet place, I will find a quiet place to work where I won’t be disturbed. I like to start about 40 minutes, normally, before any phone call or meeting. And I get into place and I organize my space, and I start to think about what might come up. And I’m just really quiet in that time and trying to induce focus.

11:50 Oscar Trimboli

For the longer brief, what are you thinking about?

11:53 Rebecca Lazenby

I want to be open and calm. I’m trying to get myself into a physical and mental state where I’m ready to listen, and I’m relaxed. And I’m not trying to think about what you might say. I’m trying to think about how I might receive it. I don’t want to second guess what you’re going to say because I need to be open to whatever’s coming. But I’m trying hard to get myself into a state where I’m ready for that.

And that means, because I’m quite an introverted person, I like to get really grounded so I have my doggy, my cup of tea, my quiet time. And really get in that space where I feel I can relax and totally focus on the other person and not how I’m feeling myself.

12:49 Oscar Trimboli

Wow, that sounds like a really thorough tuning process that Bec undertakes. I wonder what your ritual for preparing for a group meeting is. How do you tune? How do you get ready? How do you shut down the browser tabs in your own mind so you can be present? Not just to hear what they say, but to listen to what you’ve made sense of it. I wanted to share an excerpt from How to Listen, the audiobook edition, about getting ready to listen.

Prepare by tuning. When a professional orchestra prepares for their performance, they tune their instruments every time. Whether they’re playing in the same concert hall, a new location, with regular performers, or with guests, the process and practice of tuning their instruments before they begin is crucial to creating a predictable and consistent high quality performance.

Although a musician may have performed in the same building only 24 hours earlier with the identical instrument, they still humble themselves to their conductor, the audience, and their fellow performers. And tune their instruments every single time. While undertaking the tuning, they are simultaneously tuning into the sounds of the other instruments and performers. Tuning is a skill, a practice, and a strategy. Tuning is a sign of discipline, self-respect, and mutual respect.

Getting ready for a performance is about their physical presence, where they sit, how they sit, the lighting, the placement of the sheet music, and clear eye contact with a conductor. Even if an orchestra has done this thousands of times, the practice of tuning is always an act of curiosity and care. It is this process of practice that creates a mindset towards mastery.

When tuning, they are not going through the motions. It is deliberate, sequenced, and thorough. It’s not something they can fake. You either are tuning your instrument or you’re not. This is a commitment to consistent improvement and creating a memorable experience, rather than just playing music.

Professional performers will take from five to 10 minutes during the tuning process. This will vary based on the age of the instrument, their knowledge of the venue, and their familiarity with the music. When tuning, the orchestra is always tuning to the note A, usually around 440 hertz, hertz are vibrations per second, led by either the oboe or the first violin. Prepare by turning.

15:56

Bec, how would you compare and contrast your tuning ritual in a live environment where people are present, compared to doing that in a media environment via video conference?

16:11 Rebecca Lazenby

When you work in a room with people, there is a process aspect to the work that doesn’t necessarily present itself when you’re working from a text. Or you may still be working live but working on Zoom. Because people can’t see what you’re doing in the same way, the process of sense-making for them is not as strong. When you work in a room, they’re watching me organizing information. They’re watching me listen. And it can help people to see tensions, synergies, and to make sense of the conversation. It can also help them to see that they’ve been heard, which is very important for community groups, often. It can help them to see different perspectives. And make their way through a problem in what can be quite a structured way.

When you’re working from a text or via Zoom, it becomes more of an aesthetic exercise and more of a product at the end of it. There’s a differentiation between the process and the product. Working directly from a text, obviously you can refer back to the text. I read the book about three times, and then I kept dipping in and out of it to confirm my understanding as I was going along. I also listened to the audiobook, which was super helpful, because it gave me ideas about the kinds of people that I might illustrate.

And you’d already provided me with a really good understanding of who your audience was. I was able to think about people, and how to represent them so it would resonate with the readers, which is really what I’m trying to do in the room as well. I’m looking around me to draw the people that I see, and to help them to be represented in a way that’s meaningful to them. But, still, when you’re live, you can’t rewind somebody. You just have to listen and keep up.

So the listening, it’s deeper than just listening to the words, it’s listening to the whole tone of the conversation and how things are said. Because nobody is able to capture every single word that people say in real time. Though, you need to capture the sense of what is being said. And lots of graphic facilitators say the essence of what is being said. So in order to do that, it’s more than words, it’s emotions. It’s pace, tone, and all the emotion in the room, and the dynamic in the room. You need to listen to that.

So when you’ve got a text that’s quite different because you’re working from a different medium. So you have to imagine those scenarios in your mind about what might be happening when somebody doesn’t have time to listen to you. You’re creating your own world then. In a way, there’s still that intense focus, where you’re creating this little world. You live in it for a few weeks while you’re illustrating and become quite attached to the characters.

19:12 Oscar Trimboli

One of the things that’s interesting for me is, I’m usually the person taking the briefing. Somebody would ask me to participate in a project for them and support them. And, this time, I was giving the brief, which I felt enormous responsibility for. One of the questions I posed right at the beginning of our conversation was, what would make this a great conversation?

19:38 Rebecca Lazenby

And that was a fantastic, actually, because what it allowed me to do was set my expectations right at the very beginning of our conversation. I hadn’t expected you to ask me that. It was good because I was able to just give you… A bit like an agenda. I told you what I wanted right at the top. And then, in our subsequent conversation, we were able to work through those points of things that I needed to be addressed in order to do my job properly. So that really visited a whole conversation, so I didn’t feel there were any loose ends and things that we hadn’t covered.

Where we talk about purpose, audience, and design,

- What’s the purpose of the communication?

- What’s the audience for the communication?

- And then the design always flows from that.

I asked you about the purpose, where you wanted to use the drawings, whether they needed to be big, small. And then we talked about the audience. And you really surprised me because you’re the only client that has ever given me a fully developed avatar of your reader, which was enormously helpful. And you had lots of information and photos. And it was really a well-developed character for me to base my drawings on.

20:47 Oscar Trimboli

And the last part was design.

20:49 Rebecca Lazenby

From a design point of view, I had all the things that I needed to get me going, so that I felt confident that I had a good idea of what you wanted. And then we agreed that we would pick one of the chapters as a prototype.

And we picked number five as a prototype. And then we had some discussions around what that should look like. And whether we should signpost the illustration a little more clearly for people, so that they could see their way through the information on the page. And we talked about white space.

21:23 Oscar Trimboli

What you don’t know about Bec right now is, she’s in the middle of a huge renovation. And while we were doing the brief, I consistently talked about measure twice, cut once. Which meant when we picked chapter five, we were focused on chapter five, but we were also keeping an eye to the chapters ahead of that and the chapters earlier than that. And one of the things we did was iterate multiple times on chapter five, before we proceeded to do all the other chapters. It’s a significant undertaking.

This project took the best part of 90 days. And I learned a lot through the iterations. But the biggest learning I had was how to listen to what’s not said during the design process. And what I learned really quickly was the unsaid. Although Bec and I were having a marvelous conversation about the illustrations, what I needed to do was reach out to some people I knew, and some people I didn’t know, to test the drafts of chapter five. And we got some really big learnings.

Although there’s a lot of words on a page in a book, bringing the key words from each chapter, actually takes up a lot of space on a page. Helping the person with the illustration to know which way the information flows was another piece of feedback. Bec, I’m curious, what was that process like with the back and forth with me? Was it frustrating because we were staying with chapter five for so long and you were desperate to move on? Or what’s that piece like in the middle where, like most projects, we start with good intent. And then the opportunity for creation takes place, and how we start and how we finish doesn’t work out the same.

23:18 Rebecca Lazenby

It wasn’t frustrating at all. It was really helpful and supportive. I presented you, initially, with a fairly finished looking chapter five. There were things with it that needed to be changed. And when you reviewed it with your audience, they were really helpful in saying, “Look, this needs to be better signposted.”

And, “I don’t know where to start reading this. I don’t know whether it goes up or down, left or right, how it flows.” Even though there was a natural flow in the diagram, we needed to make it more obvious.

Now, because you know the information really well and I know the information really well, because I’ve read the book so many times now, the flow of the information to me was really obvious. But to somebody who’d never seen that before, it wouldn’t be. So we decided to put in that helpful signposting. And then I tested it with a couple of people too. And I showed them ones without that and ones with it. And they all really liked the ones with… They found it helpful to have that clear signposting.

I don’t find the backwards and forwards nature frustrating because it was constructive. And it helped us, taking that time up front to get that chapter right, helped us speed up doing the rest of the chapters.

Because there were eight in total, so there were seven more drawings to do. If we hadn’t have done that, it would’ve taken much longer to complete those, if we hadn’t have put in the initial legwork on that first prototype chapter.

25:01 Oscar Trimboli

That was my really big learning too, the signposting is to use numerics. There’s sequence in numerics that people understand one starts here and then two goes there. The other piece of feedback was about, “Oscar, the information’s too dense. Give me some space to explore the idea a little further.” Again, face-to-face, the specificity is the playback of actual verbatim from people there. And I think this is one of the differences between live illustration and then illustrating the book.

25:40 Rebecca Lazenby

In some scenarios, when you’re working live, you can turn around and ask a clarifying question. And say,

- “Does this make sense where I’ve put this?

- Should this be over here?

- Should it be connected?

- How should this be connected?”

And people will engage with the work in that way. We didn’t have the luxury of that real time feedback. But I think that there wasn’t just a numerical sequence. There’s also a hierarchy in the design, the chapter headings, and then use some of the pull quotes. And I’ve written them in a different style to indicate where those things change.

White space part of it was just tricky because some of the chapters had so much information. What I had to do was reread the chapter and pull out what I thought was key. And then float that with you and then see whether we needed to add or take away. And, normally, we took more away. It relieved some of the pressure of trying to fit all those things in. Some things need to be spelled out with text. You can’t make everything into a graphic. But there were some things that I was able to synthesize down into a graphic, or make a little model of, which was a bit of a shortcut for the idea.

27:01 Oscar Trimboli

I’m fascinated about the physicality of you listening. Describe fully for somebody who’s never had an illustrator present in a group setting, describe the size of the paper, and the markers, and the stencil outlines, and the process that you’re going through? And then contrast it to digital which, to me, the format drives a very different interaction with the idea. Talk us through the physicality of setting up for a live illustration and contrast that with a digital version.

27:38 Rebecca Lazenby

I’ll tell you my ideal physical setting then. It’s a room with very smooth plaster walls. And there’s no tables, there’s only chairs in a circle for the participants. And I will go into that room, hopefully the day before.

And I will wallpaper that room from floor to ceiling. And I have a ladder. And I will work, floor to ceiling, all the way around the room. I work really large scale. If we had a one-day meeting, I would get most of the way around the room.

There’s a kinesthetic aspect to the work which is profoundly relaxing, so you are listening and moving. The only thing you are doing is concentrating on what’s being said. And you’re in a flow state. Even though it’s incredibly hard work physically to keep going all day, there is something profoundly magic about doing that work. I don’t mean it’s magic in the way that it’s amazing.

The actual process of doing it, of listening and drawing at the same time. I’m never as relaxed in my life as when I do that work.

When you work as a contrast to that, when you work digitally, for me, not for other people, but for me, when I first started working digitally, I found it so frustrating.

I’ve got an iPad the size of A4. The pens respond in a completely different way. There’s no movement in your body, so you’re really fixed in place. And it feels really constrained to me. Also, because of the way people interact on Zoom, and the whole way a conversation goes, you have to put your hand up.

You have to wait for someone else. You don’t get the normal cues of when you’re having a normal conversation with people. To me, things become more soundbite-y. There is a different level of engagement with the participants and from me. And I think it is more constraining. And it takes a skilled host to navigate all those tensions when you are working via video conferencing.

29:52 Oscar Trimboli

We’ll just do a little process check. What have you noticed about my listening?

29:57 Rebecca Lazenby

I have noticed that you have your camera perfectly positioned so you are looking straight into my eyes. I feel like I’m talking to you because it looks like you’re looking right at me.

30:10 Oscar Trimboli

And is there anything else you’ve noticed?

30:13 Rebecca Lazenby

You ask good follow-up questions. When I’ve said something, you don’t just ask a question that you have been planning to ask me.

We’ve definitely diverged from…

We talked about what we might talk about, and we have diverged from there as a result of different things that I’ve said.

Because you’ve listened and you’ve followed that thread, so you’ve been open.

30:33 Oscar Trimboli

Bec and I deliberately set aside time where we debriefed. How did we go? What would we do differently? And my biggest learning from this process was I didn’t provide a clear enough brief for Bec in terms of design. We’re going to use these amazing illustrations for each chapter to help people understand on social media what the book’s about.

Yet in doing that, I constrained myself. Bec, again, in face-to-face, real time, at the end of the workshop, there’s a process that happens as people step away and interact with the illustration, which isn’t true in virtual environments.

31:29 Rebecca Lazenby

When you work live, there is a natural winding down. People drift away. Some people come over to chat and have a look at what you’ve done. But I actually always ask specifically for feedback afterwards.

And that comes from learning how useful that was. I worked in a small team where we had a routine, where we sat down, no matter how long we’ve been working, how tired we were, we sat down and we had a structured debrief. And it was probably the most high performance team I’ve ever worked in, largely down to the feedback that was solicited that you could then make the next time better.

When you work live on a Zoom though, quite often, it’s just, “Okay, we’ve run out of time, everybody. Thanks, everyone. Bye.”

And then it’s off. And I’m sitting there, and I’ve been listening really hard, not moving, for four and a half hours or five hours.

And then, suddenly, it’s just switched off. And, actually, you feel a bit bereft, like it’s just vanished.

And you just sit there. And then it’s very hard to follow up and get any closure at all. With a job like yours, where I’m doing an illustration and we’re getting feedback along the way but, at the end, I asked you specifically for feedback about anything I could have done better.

32:52 Oscar Trimboli

I’m super curious about this high performing team environment with structured feedback sessions. What were the questions we could learn from and use in other environments that were quite memorable from those structured feedback sessions?

33:07 Rebecca Lazenby

Oh, with a question, what did we plan to happen? What actually happened? If we’d have done this, what would’ve made it even better?

So those were the three questions which, really, quite open questions that allowed quite a ranging conversation. And it could be anything from, “Please don’t wear that purple shirt again.” Or something about access to the room.

33:36 Oscar Trimboli

Just in that environment, I’m visualizing three to five people doing this structured debrief.

- Was there process around time?

- How did the group interact?

- Who kicked it off?

- And what was the process to ensure the embedding of that learning in the next workshop?

33:56 Rebecca Lazenby

We took it in turns to kick the process off, and there were usually three of us. In terms of timing, often, we did keep it short because we’re all really tired, probably been in the room a couple of days.

Then is exactly the right time to do it because it is all top of mind. And that is your chance to unpack it a bit and it does give you some closure on the event too. Afterwards, we formalized those, just by typing them up. And then we reviewed them for next time so that we made sure that anything we said, “It would be better if we did X, Y, and Z,” then we would follow that up and make sure that we did do that.

34:37 Oscar Trimboli

In terms of process, were all three questions asked at the beginning or you did question one?

34:43 Rebecca Lazenby

Yeah, one by one. And we had a little sheet, and the person running the process would just scribble down some notes as we went.

34:53 Oscar Trimboli

Now, one of the things I always talk about with leaders when I’m observing, they’re running their team meetings, and it’s critical point Bec made.

She reflected on the most high performing team she’d ever been part of took this reflection time. It should be between 10% and 15% of your allotted time. And it doesn’t have to wait till the end of the meeting, the workshop.

It can take place midway. As a leader, if you’re running regular weekly team meetings, one in four of those meetings, you should be reserving 15% of the time, not necessarily at the end, to ask the group a version of those three questions that Bec outlined. It will improve your performance as a host. And, more importantly, it will improve the performance of the group.

The final magical piece in this process that Bec talked about is, it is integrated into the next version of the meeting, the next version of the workshop in her case. And that is often the bit that’s missed.

Great hosts announce the actions from the last meeting and the stage of completion, before the meeting goes into the new agenda, to ensure that the group knows you’re all about embedding the learnings.

And that will increase the performance of the team. Bec, let’s use your three questions to analyze the project we’ve just gone through.

36:27 Rebecca Lazenby

What should have happened? I was supposed to illustrate eight chapters of your book in a way that helped you connect with your audience, some who may have already read the book and some who may not.

The illustrations also needed to be able to stand on their own without being embedded in the text. If you put them up on LinkedIn or some other platform, or just printed them and left them for somebody in a workshop, they would be able to understand them without having the book by their side.

From a timeline, we said about a month, and so it should have happened in about a month. And then what actually happened was I did do eight drawings. They do stand alone. They do support the text.

I think they’re suitable for readers and people who have yet to read your book. But it took more than a month. I needed to develop a better understanding. I should have quizzed you more about what you were planning on doing with the drawings. You wouldn’t have the conundrum because of their shape, which they are now a bit long.

How do we work through that now? And that is a more difficult thing to solve when the drawings are done, than it would’ve been if I’d have had that in my mind to start with about what the length of them should have been. What the format should have been.

Though, I didn’t give myself enough space in between each one, the time that I took to do the first one, when I took out the iteration time, but the time that I took was nowhere near. I probably took double the time on each one. A, I underquoted time wise. And B, I needed more space in between them anyway because I couldn’t just finish one and go straight onto the next.

I needed to walk away, reflect, have a bit of a read of the next chapter, and get ready to do the next one. And I didn’t leave myself enough space, so I had to ask you for an extension of time. About three weeks, I think it was, extra. I could have been more realistic about the time it was going to take me.

38:34 Oscar Trimboli

And my build on that would be, what I would’ve done differently, is rather than just having a text or telephone interaction with you at each chapter, iteration, possibly just having a formal 30-minute call, asking the three questions you’ve just described. And I think that would’ve helped to improve our performance.

What did I take away from this conversation? Four things.

- expressing the key concepts in this paperback book should have taken place when I’d completed the manuscript process, rather than 12 months after the anniversary of the book. I suspect without getting feedback from the readers and the listeners, it’s unlikely this idea would’ve come to life.

- expressing the key concepts through a visual medium helps to engage with the ideas in a really powerful way that helps the readers understand where they’re at in making sense of the idea, just not how I’m expressing the idea.

- I needed to be more open about the project. And the idea should have been available in more formats than just, “Hey, Bec, let’s create something that we can share on social media via LinkedIn.”

- the teamwork between the illustrator and the author, it evolves over time. I think what I did well was I was open to change. And Bec and I were willing to adapt as we went along. We weren’t fixed in what we wanted to do. We were pretty obsessed with what will be useful for the readers, the people who are trying to make sense of the idea.

If you want to access the printed and/or digital versions of the award-winning book, just visit www.oscartrimboli.com/summary

I wonder what you took away from this conversation. What will you do differently in your next complex project, in your next complex group meeting, as a result of listening and watching today?

Please send me an email, podcast@oscartrimboli.com, with your reflections.

You will have noticed, because I was getting feedback from the readers, the difference between hearing and listening is the action you take. And as a result, we’ve created this artifact for you to help make sense of listening.

I’m Oscar Trimboli, and along with the Deep Listening Ambassador Community, we’re on a quest to create 100 million deep listeners in the workplace.

And you have given us the greatest gift of all, you’ve listened to us.

Thanks for listening.

42:01

Thanks for listening this far. As a bonus, I wanted to share with you two things. The first one is, recently, I was speaking to a book club in India, the She Reads Book Club. Thank you very much for your support. And one of the questions from the members there was, “Oscar, could you tell us why the subtitle and title of the book are in lower case?” And my reply was, “Simply speaking is uppercase and listening is lowercase. Both must exist for communication to be present, and one cannot exist without the other.” It’s about balance, rather than one being correct or incorrect. I know I’ve had a number of emails as well where I’ve responded to the people who’ve sent that. But I thought I’d share that with you who’ve taken the time to listen.

And then, finally, I would like to share with you a little reminder from episode 18, where we interviewed public listener and visual scribe, Anthony Weeks. Who, not surprisingly, despite the fact he’s on another continent, is good friends with Rebecca Lazenby. And he talked about how to listen in capital letters. And this quote stays with me for a long time.

43:24 Anthony Weeks

Points of inflection, or points of emphasis, where if you could visualize it in your mind, they would be saying them with capital letters.

And so listening for those capital letters to say, “Ah, that’s it. That’s what they really mean to say.”

Or, “That’s important to them. I’m going to write that in capital letters because that sounds like it’s a big deal.”

And I think that, sometimes, when I’m listening, listening, listening, people will set up something by saying, “So what I really mean to say is…” And that’s just a softball. That’s really easy. It’s like, “Oh, okay, I got that.

They’re ready to say something important.” But, sometimes, it’s more subtle. Sometimes, it’s more they’ll be saying something, and then they’ll sigh, and they’ll stop. And they’ll give a moment of silence, and then they’ll say what they really want to say.

And so when you listen for those cues, and when you listen for those points of direction, where somebody is about to say what’s really important to them, then I think you get a little bit more attuned to listening for the capital letters. And listening to the meaning that they’re about to provide you.